Sources

Note: THE author desires to

express appreciation for the kindness of many people who have cooperated in preparing

this history. In particular, gratitude is due: Mr. Channing Howard, Mr. Sidvin

Frank Tucker, Mr. Frank K. Hatfield, Mr. Brendan J. Keenan, Mrs. Sarah L.

Whorf, Rev. Laurence W. C. Emig, Rt. Rev. Richard J. Quinlan, Rev. R. S.

Watson, Rev. Ralph M. Harper, Mrs. Alice Rowe Snow, Rev. H. Leon Masovetsky,

Mrs. Emilie B. Walsh, Mr. Charles A. Hagman, Miss Dorothy L. Kinney, Sgt. Paul

V. Albely, Mrs. Mary Alice Clark, Mr. William F. Clark, Mr. Preston B.

Churchill, Mr. Benjamin A. Little, Mr. Joseph F. O'Hern, Jr., Mr. Eugene P.

Whittier, Mr. Albert J. Wyman, and Mrs. Evelyn Floyd Clark.

-----------------

INDEX TO ILLUSTRATIONS

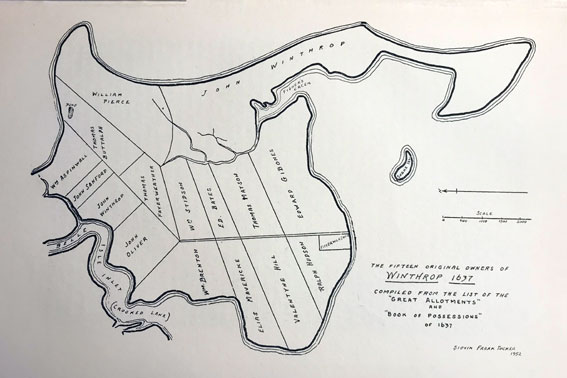

Map of Winthrop, 1637 69

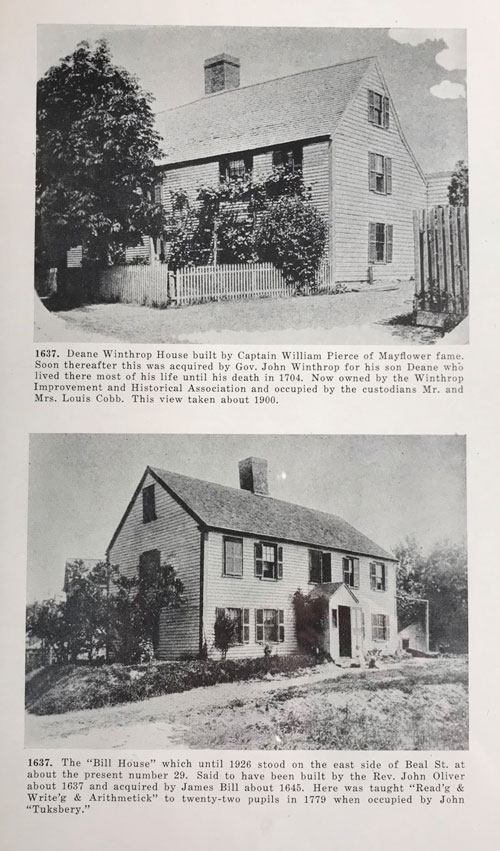

Deane Winthrop House, 1900 (1637) 84

Bill House, 1926 (1637) 84

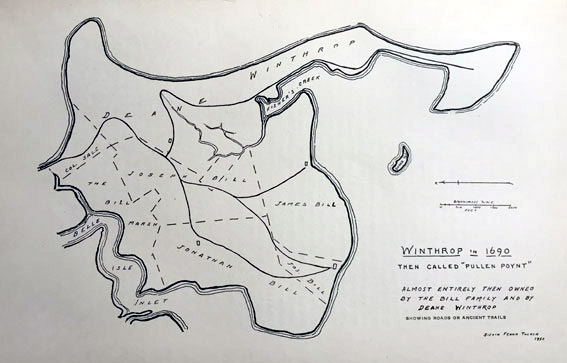

Map of Winthrop, 1690 87

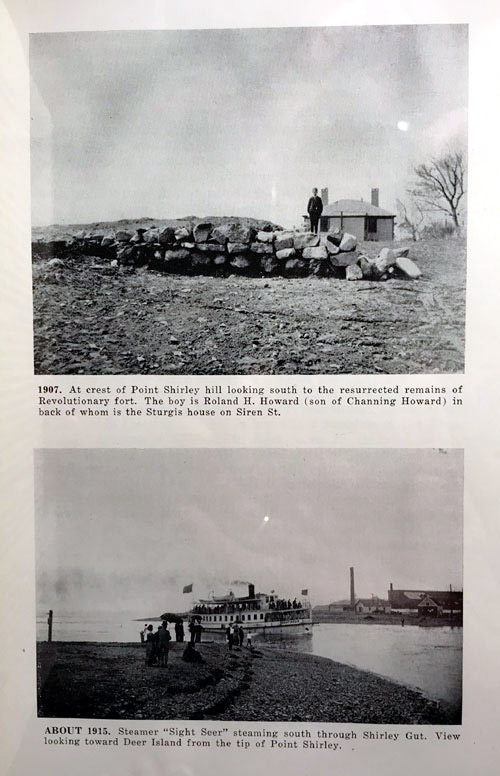

Revolutionary Fort at Point Shirley, 1907 136

Shirley Gut, 1915 136

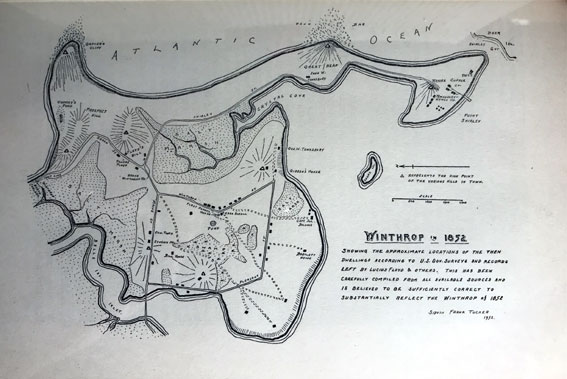

Map of Winthrop, 1852 145

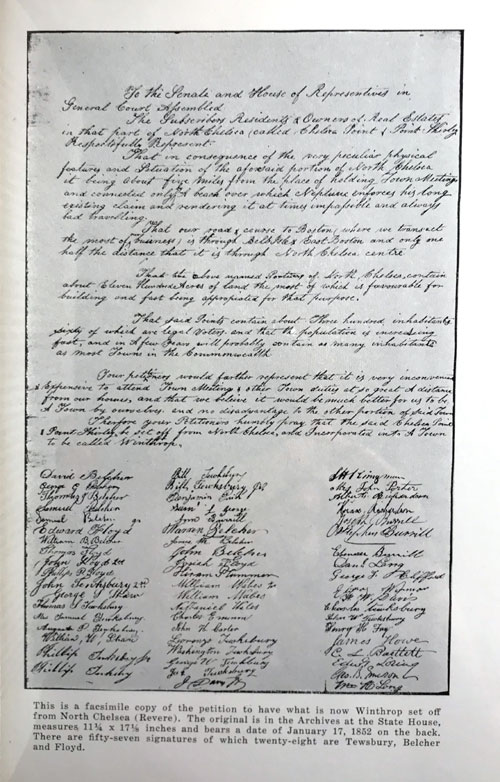

Petition to lncorporate the Town, 1852 146

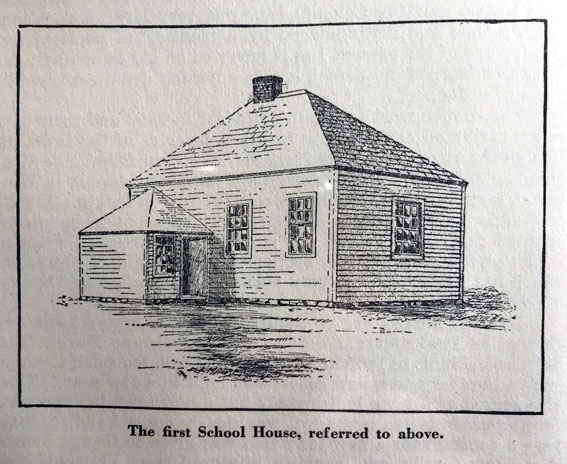

First School House, 1852 148

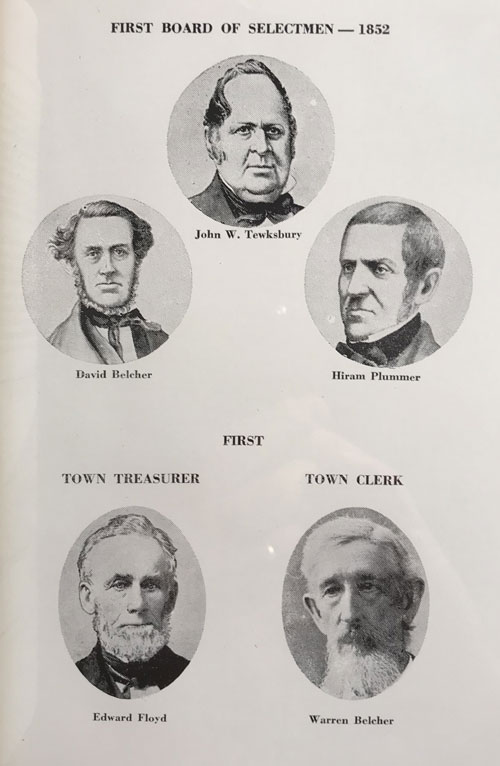

First Town Officers, 1852 148

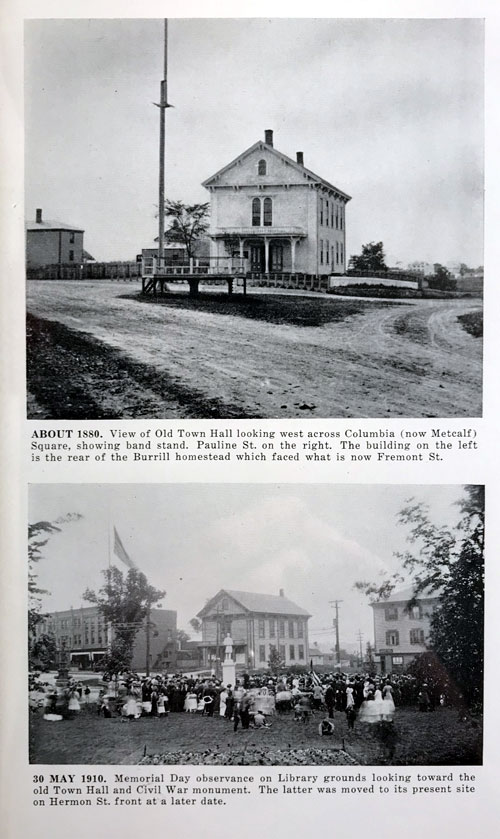

First (Old) Town Hall, 1880 150

Memorial Day, 1910 150

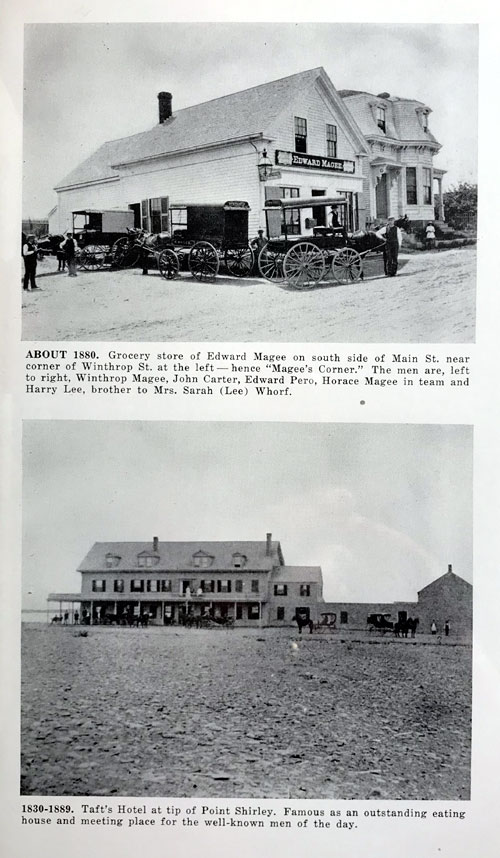

Grocery Store of Edward Magee, 1880 156

Taft's Hotel, 1830-1889 156

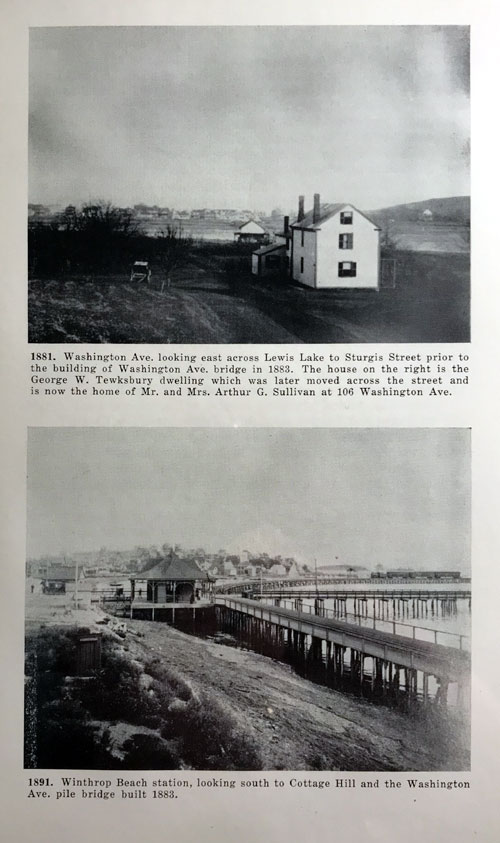

Washington Ave., 1881 168

Washington Ave., 1891 and Winthrop Beach Station 168

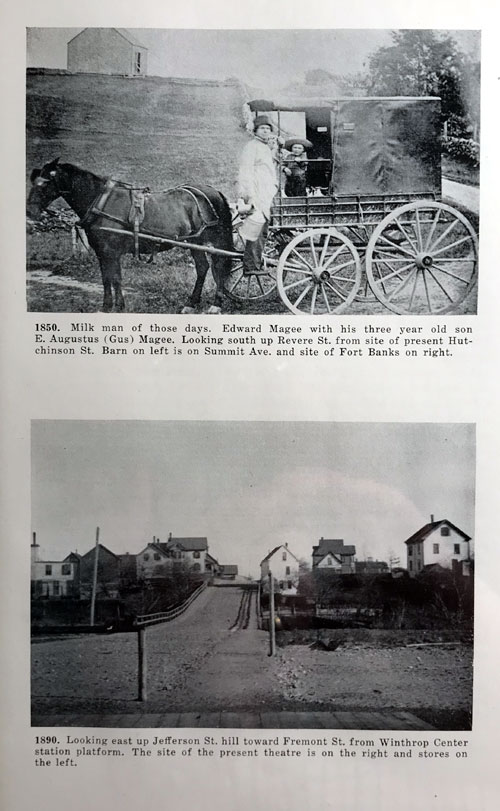

Milk Team on Revere St., 1850 178

Jefferson St., 1890 178

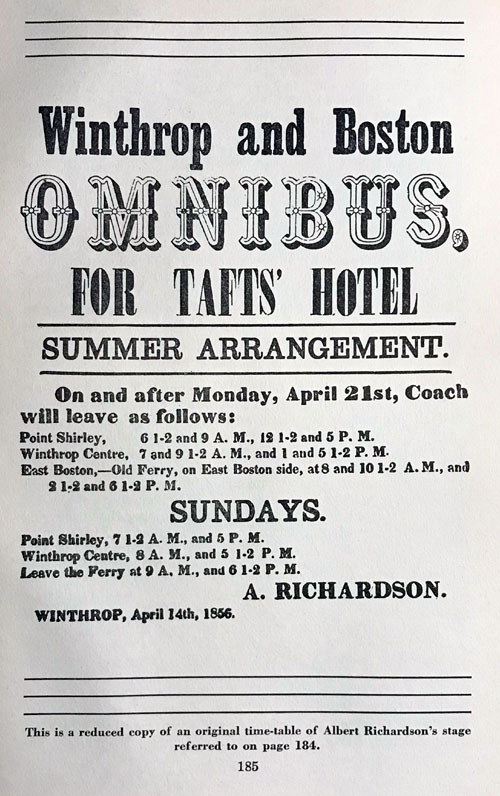

Omnibus Time Table, 1856 185

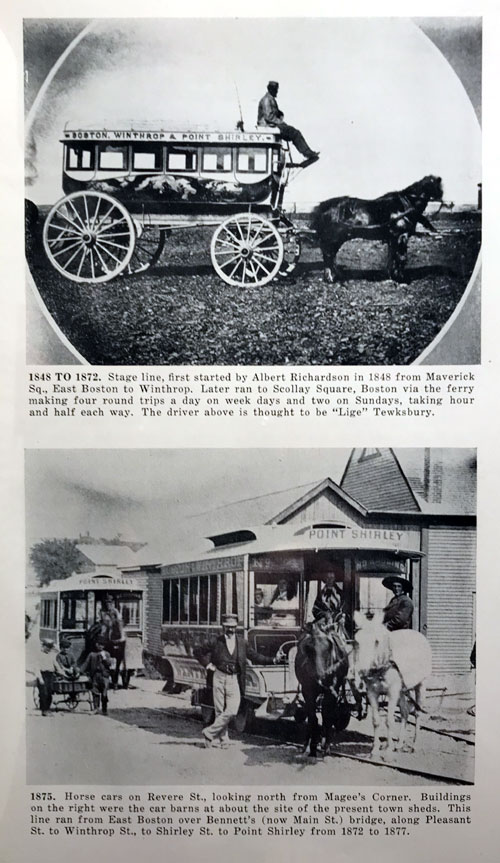

Stage Coach, 1848-1872 186

Horse Cars, 1875 186

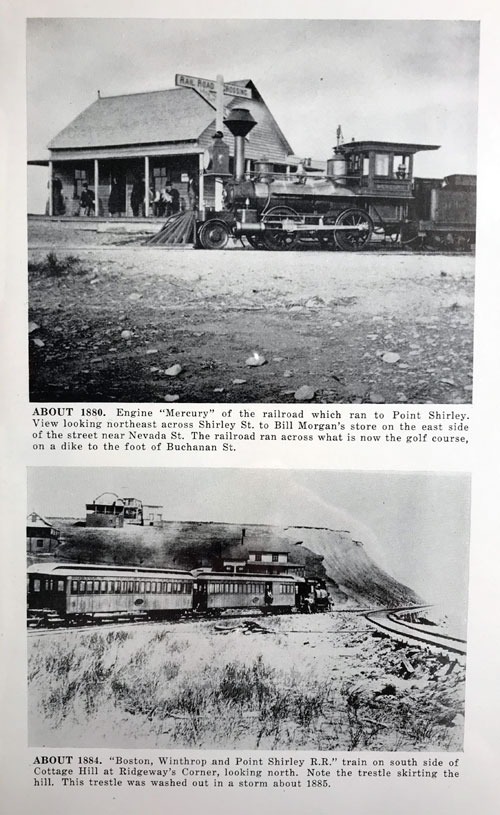

Engine "Mercury", 1880 192

"Boston, Winthrop & Pt. Shirley R.R." Train, 1884 192

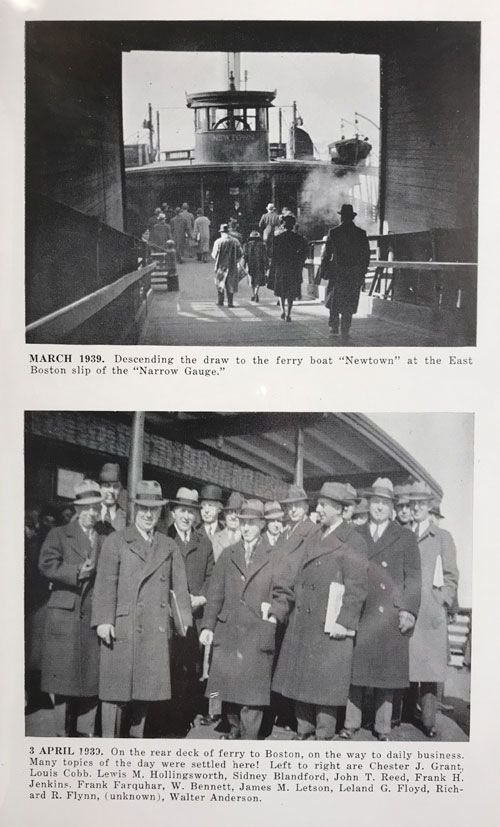

Draw to the Ferry Boat "Newtown," 1939 194

Group on Rear Deck of Ferry, 1939 194

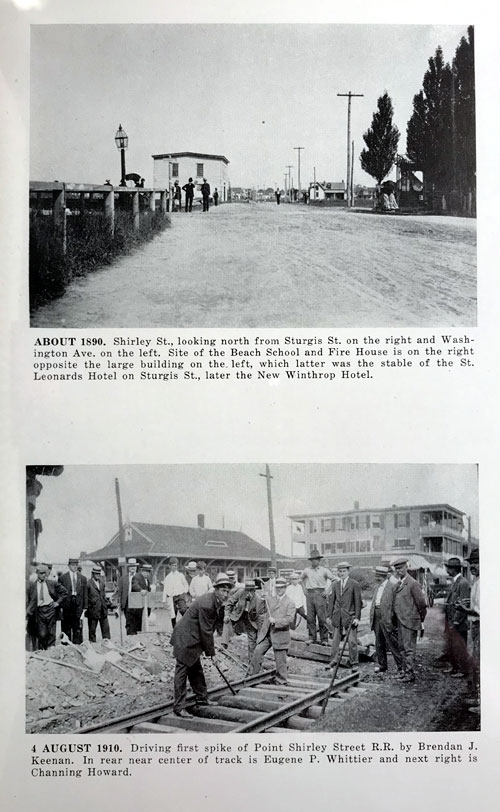

Shirley St. at Sturgis St., 1890 196

First Spike of Pt. Shirley St. R.R., 1910 196

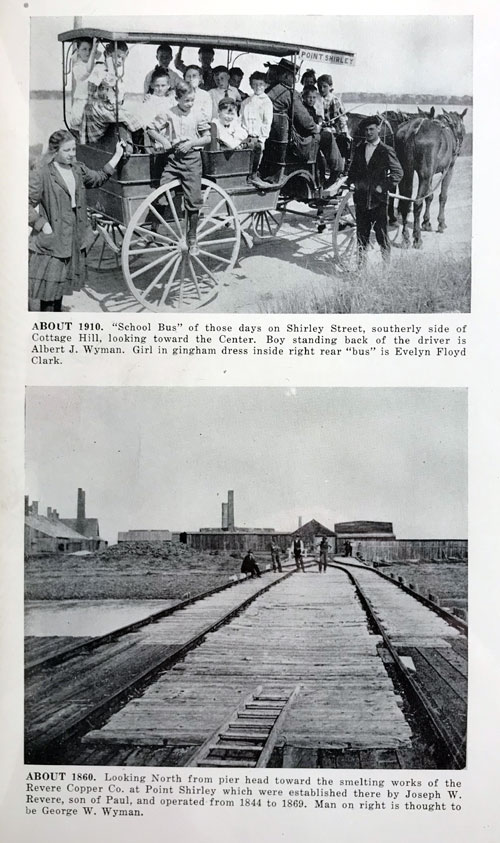

"School Bus" from Pt. Shirley, 1910 200

Copper Works at Pt. Shirley, 1860 200

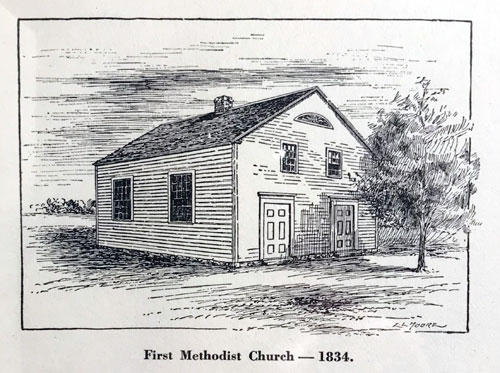

First Methodist Church, 1834 203

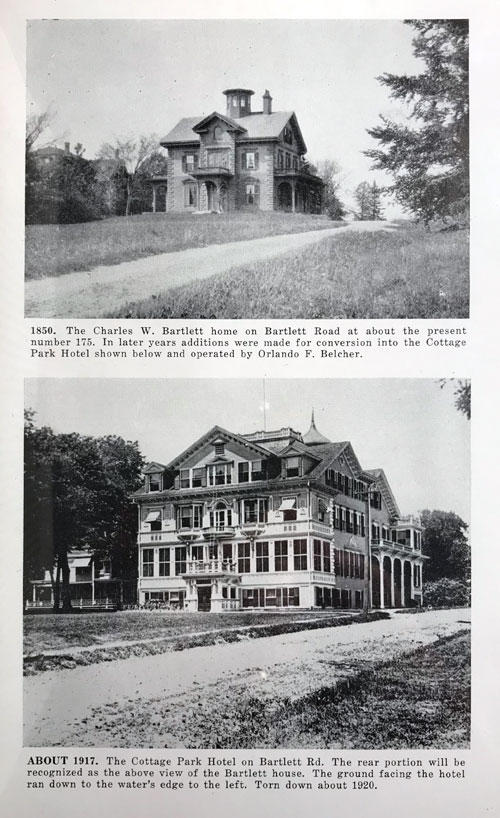

Bartlett House, 1850 226

Cottage Park Hotel, 1917 226

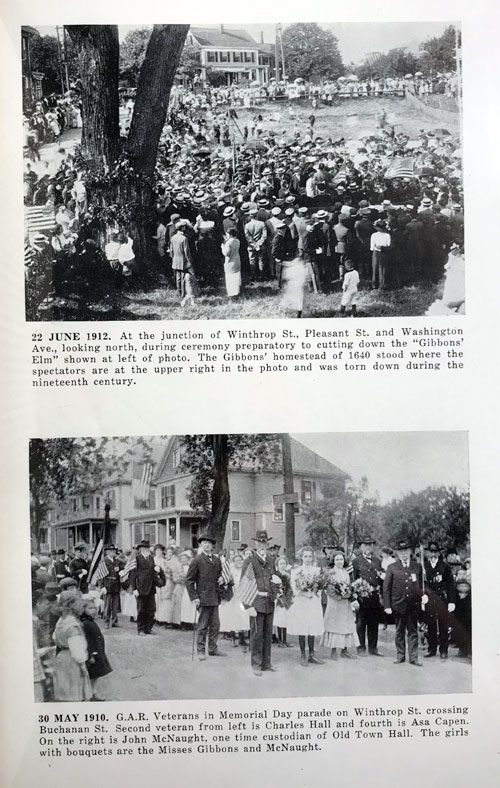

"Gibbons' Elm" Ceremony, 1912 230

G. A. R. Veterans, 30 May, 1910 230

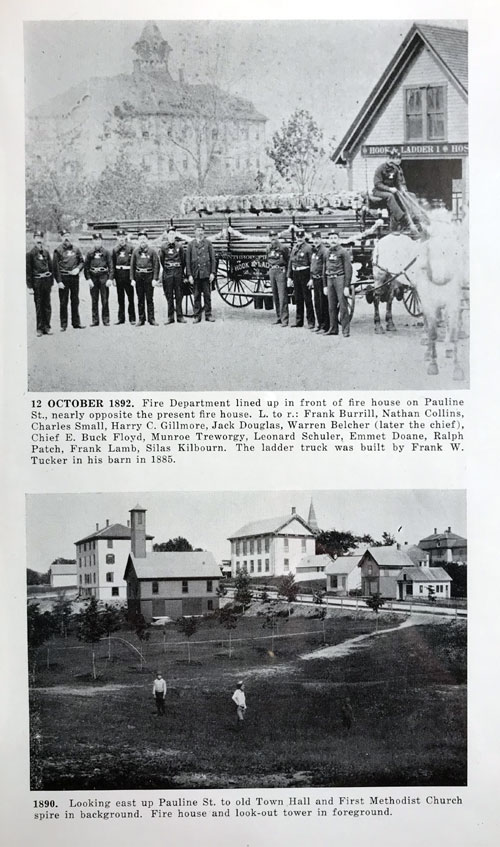

Firemen and Ladder Truck, 1892 262

Pauline St., Town Hall and Fire House, 1890 262

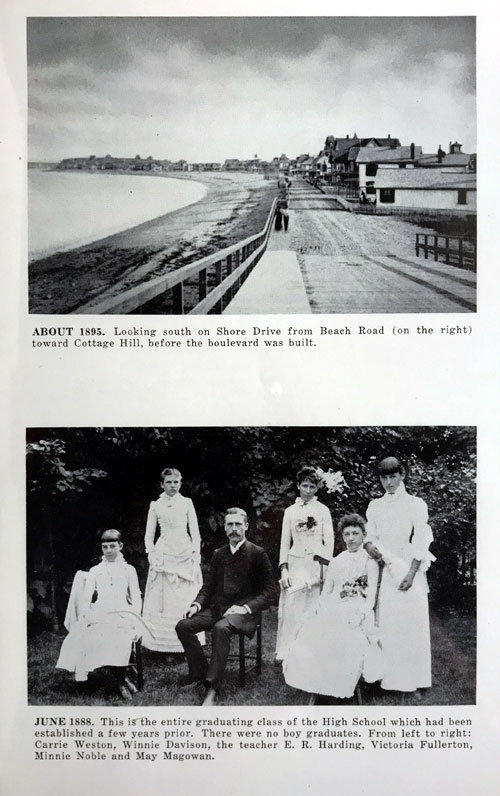

Shore Drive, 1895 276

High School Graduates, 1888 276

CONTENTS

CHAPTER PAGE

Foreword

1 Geography and Geology 3

2 The Indians 26

3 John Winthrop 47

4 Discovery and Early Settlement 53

5 Colonial Development of Winthrop 80

6 Point Shirley 89

7 The Town of Chelsea 95

8 Winthrop Up to the Revolution 100

9 Winthrop in the Revolution 125

10 The War of 1812 141

11 Winthrop in the 19th Century 143

12 Transportation 181

13 Revere Copper Company Works 199

14 Winthrop Churches 202

15 The Second Fifty Years 223

16 Winthrop Public Library 251

17 Winthrop Pageant Association 254

18 Winthrop Newspapers 257

19 Police Department 259

20 Fire Department 262

21 Yacht Clubs 264

22 Winthrop Banks 270

23 Winthrop Schools 273

24 Winthrop Community Hospital 289

Appendix A - Annals of the Town 301

Appendix B - Town Officers 307

-----------------

Foreword

YOUR Anniversary Committee takes great pleasure in

presenting the first complete history of our Town.

It has long been a matter of regret by our citizens that

the historic events credited to our Town have never been chronicled and

published. The author, Mr. William H. Clark, has long been recognized as

outstanding, particularly in the field of historical writings. A former

resident of our Town, he has devoted a great deal of time in intensive research

necessary to the production of a work of this importance.

Planning many events to celebrate the 100th Anniversary of

the granting of the Charter to our Town, the Committee feels that the

publishing of this volume will be the most important. Other events scheduled

will pass on and become but memories, but the History will be a permanent

memento of the Centennial celebration of our fine New England community.

History Committee

BRENDAN J. KEENAN, Chairman

FRANK K. HATFIELD

SIDVIN FRANK TUCKER

-----------------

Chapter One

GEOGRAPHY AND GEOLOGY

SITUATED almost due east of down-town Boston, within clear

view of the Golden Dome of the State House on Beacon Hill, the town of Winthrop

is one of the smallest communities in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. This

is so in point of size alone. On the town's one thousand and seventy-five acres

some eighteen thousand people live -- thus making the little town by the sea

one of the more important of the State.

Winthrop, is a beautiful town. Its location between the

Atlantic Ocean on the East and Boston Harbor on the West is alone enough to

establish the fact. Even more, Winthrop is a town of gentle hills which,

although now built over with about 4,000 houses, gives almost every window a

wide prospect over miles of ocean, marsh and a city just far enough away to be

remote and yet near enough to be conveniently reached within a half-hour or so.

Probably one of the greatest factors concerned in the production of Winthrop's

charms are the many elms and maples lining her 36 miles of streets and shading

most of her homes and all her public buildings.

There are wealthier towns in the Commonwealth than Winthrop

but few more financially fortunate. By many years of self-sacrificing service by

public-spirited citizens who have served the town largely without pay, the town

is practically without debt; nearly all the streets are paved and have

sidewalks while the municipal establishments, schools, library, town hall, fire

houses and all the rest are paid for in full.

Winthrop is known as a town of homes. This is true because

there is practically no industry in the town at all. The town is emptied of

mornings by perhaps ten thousand men and women who go into Boston to their

various occupations. At evening, they return home. This is a common condition

of many of the suburbs around Boston and certain uncomplimentary critics have

described these suburbs of Boston as being mere bedrooms for the City.

However true this may be, Winthrop does maintain its own

spirit and integrity. As it is a pleasure to live in Winthrop, so is it a

distinction. This is the result of the town's many years of

3

history, a history free of the scandal and difficulties which have affected at

one time or another, most of Boston's suburbs.

This is remarkable, because Winthrop has a long, long

history. Actually, this town observes its centennial this year. That is so

because it became legally a separate town in 1852, when it was parted from the

present City of Revere. Previously, Revere (and Winthrop) had been a part of

the present City of Chelsea -- just as Chelsea (and Revere and Winthrop) had

been a part of the original settlement of Boston.

That takes the history back to 1630 but this is merely the

white occupation of this area. The first whites who visited Boston Bay of

demonstrable certainty were hardy fishermen from Britain, France and Portugal.

These doughty seamen came here to catch the great cod which then flourished in

great numbers. In tiny vessels, hardly more than present-day yachts, they

sailed westward in the Spring, landed a few men on shore, in such bays as

Boston Harbor and built huts. 'Then, while the rest of the men fished, the

shore detail dried the fish in the sun, made barrels into which they packed the

fish and did some trading with the Indians, exchanging trinkets and liquor

worth a few pence for furs worth great price. Then, when the Fall storms came,

the fishermen sailed home with their fish and furs. This business' certainly

flourished during the latter part of the fifteen hundreds and these fishermen

were often on hand to welcome the "discoverers and explorers" when

they arrived somewhat later.

There is a reasonably good probability that there were

white men here even before the fishermen. These were, of course, the Vikings or

Norsemen who did sail along the Nova Scotia and New England coasts in and about

the year 1,000. The Norse sagas describe settlements made somewhere along

shore, tell of the battles with the Indians and while they cannot tell of the

gradual extinction of the colonies, the tragic fate of these first settlers in

America is grimly for shadowed in the poems. There is some evidence that Irish

explorers may have visited New England also at about the same era. The trouble

is. no trace exists of these primary colonies. There are opinions, of course,

but no definite proof has been found -- nor does it seem likely that such will

ever appear.

No one has ever found proof that the Norse ever visited

Boston Harbor -- but it seems unlikely that the little dragon ships of the

Vikings, coasting down from Nova Scotia, could have missed Boston Harbor as

they explored on to the south. Thus it is probable that the Norsemen must have

at least visited Winthrop's beaches and found refreshment and rest in our

forests while they enjoyed the abundance of game and sea-food then blessing

this region.

4

Before the white men, Winthrop was, of course, home to Indians. Indeed, the

future town, with its wealth of fish, clams and lobsters, was a favorite resort

in the summer for many Indians who apparently were seated in the hills back

from the shore during the winters. There is some evidence of importance that

the tribesmen the Puritans found here, were not here very long, being

comparatively newcomers. Lacking a written language, indeed any language which

would have made accurate history possible, the story of the Indians can only be

pieced together out of legends and some archeological material. This last is

very scanty, too, for the Indians, being very primitive people, had little of

permanent importance to leave behind when exterminated by the whites.

It is likely that the Indians here in 1600 were

interlopers. They seem to have been fierce and warlike people who drove up from

the south-west and forced the then holders of this area northward along the

shore. It is considered probable that the evicted Indians may be the present

day Esquimaux, or at least have been absorbed into the Arctic tribes. And there

is some further evidence that even the exiled people were not the original

inhabitants of this area, for some recent archeological studies have given

evidence of the presence of a people of great antiquity. Because these people

dyed their skeletons before burial with a red pigment, they are known as the

Red Paint People. Almost nothing is known of them.

Winthrop, when the first white people came here, was a

place of striking beauty. This is made clear in the accounts of those first on

the scene. Unfortunately, there were few Puritans sufficiently interested to

write in any detail of the geography - or indeed of anything save the formal,

legal records. Men were commonly not educated in such facilities in those days,

articulateness was not a characteristic of the early 17th century. Even so, the

men who could write were much more concerned with winning homes and

establishing a commonwealth. They were too busy to write, even if they could

have done so.

The important things about these descriptions is not so

much that they were mere off-hand comments, fragments of a few sentences

included in writing of much graver material, as that one and all they were

markedly enthusiastic. For example, the Puritans wrote home from Boston in

glowing terms. One worthy wrote: " ... So pleasant a scene here they had

as did much refresh them; and there came a smell off the shore like the smell

of a garden." It must have been pleasant and refreshing. Imagine a weary,

endlessly-long tossing upon the ocean, cramped and confined, ill and sick of

the horrible food which alone was possible on long voyages in those days. And

then to

5

see the green hills around Boston Bay, rich with heavy forests, and to look

overs ide and see the translucent water, filled with fish. Probably at morning

and again at evening, deer would come out of the forest and stand on the beach

to see what manner of creature was disturbing their peace. Then to land on the

beach, to walk on solid ground once again and to feast on fresh meat and to

enjoy the strange but delicious flesh of lobsters -- and even to have a plate

of steamed clams -- not to mention great steaks of familiar fish such as cod.

Of these fish and these sea-foods, a colonist, Francis

Higginson, wrote, "The abundance of sea-food are (sic) almost beyond

believeing and sure I should scarce have believed it, except I had seen it with

mine own eyes. I saw great store of whales and grampusses and such abundance of

mackerels that it would astonish one to behold, likewise codfish in abundance

on the coast, and in their season are plentifully taken.

"There is a fish called bass, a most sweet and

wholesome fish as ever I did eat; it is altogether as good as our fresh salmon

and the season of their coming was begun when first we came to New England in

June, and so continued about three months' space. Of this fish, our fishers

take many hundreds together, which I have seen lying on the shore to my

admiration; yea, their nets ordinarily take more than they are able to haul to

land, and for want of boats and men they are constrained to let many go after

they have taken them, and yet sometimes they fill two boats at a time with

them.

"And besides bass, we take plenty of scate and

thornbacks and abundance of lobsters, and the least boy in the plantation may both catch and eat what he will of them. For my own part, I was soon cloyed

with them, they were so great and fat, and lucious. I have seen some (lobsters)

that weighed sixteen pounds; but others have, divers times, seen great lobsters

as have weighed twenty-five pounds, as they assure me. Also here is abundance

of herring, turbot, sturgeon, cusks, haddocks, mullets, eels, crabs, mussels

and oysters. Besides there is probability that the country is of excellent

temper for the making of salt; for since our coming, the fishermen have brought

home very good salt, which they found candied, by standing of sea-water and the

heat of the sun, upon a rock by the sea-shore; and in divers salt marshes that

some have gone through, they have found some salt in some places crushing under

their feet and cleaving to their shoes."

Francis Higginson, who incidentally was a minister and thus

a man in whose writing confidence can be placed, also had this to say of the

native plants and the behavior of crops: " ... the aboundant encrease of

corne proves this countrey to be a

6

wonderment. Thirtie, fortie, fiftie, sixtie, are ordinarie here; yea, Joseph's

increase in Egypt is outstript here with us. Our planters have more than a

hundred fold this yere... What will you say of two hundred fold and upwards? Our

Governor hath store of green pease in his garden, as good as ever I eat in

England. Thecountrie aboundeth naturally with store of roots of great varietie

... , Our turnips, parsnips, and carrots are here bigger and sweeter than is

ordinary to be found in England. Here are store of pomions (squash), cowcumbers

and other things the nature of which I know not .... Excellent vines are here,

up and down the woods. Our governor (John Winthrop) hath already planted a

vineyard with great hope of increase. Also mulberries, hurtleberries, and hawes

of whitethorn filberts, walnuts, smallnuts, near as good as our cherries in

England; they grow in plentie here."

The Reverend Mr. Higginson's botany and horticulture may be

slightly awry but there can be no mistaking the fact that the settlers found

Boston a fair and pleasant land and one which was fruitful in the bargain.

Another excerpt, from an unknown writer, has this to say

along the same line: " ... This much I can affirm in general, that I never

came to a more goodly country in my life. . .. it is very beautiful in open

lands mixed with goodly woods, and again open plains, in some places five

hundred acres, some places more; some less, not much troublesome for to clere,

for the plough to go in; no place barren but on the tops of hills; the grasse

and weedes grows up to a man's face; in the lowlands and by the fresh rivers,

abundance of grasse, and the large meadows without any tree or shrubbe to

hinder the sith. .,. Everything that is here eyther sowne or planteth,

prospereth far better than in Old England. 'The increase of corne here is farre

beyond expectation, as I have seene here by experience in barly, the which

because it is SO' much above your conception I will not mention. . .. Vines doe

grow here plentifully laden with the biggest grapes that ever I saw; some I

have seen foure inches about ... "

This gentleman may have been a bit enthusiastic, but again,

he was pleased with his new home.

One of the better sources of information about the early

days of Boston and vicinity is William Wood's New England Prospect. Wood spent

some four years in this neighborhood and published his book in 1634 at London.

It is one of the best sources of information about the Massachusetts Bay

Colony, if for no other reason, it being the only thing of its kind. In Wood's

book appears a fair map of this area on which for the first time Winthrop's

former name of Pullin Point is shown, together with

7

the name of Winnisimmet, which is the original name for Chelsea and Revere.

Wood had this to say, in part, about his new home. Speaking

of strawberries, he alleged, the colonists "may gather halfe a bushell in

a forenoone ... verie large ones, some being two inches about. In other

season, there are Gooseberries, Bilberries, Rasberries, Treacleberries,

Hurtleberries, Currants ... the (wild grapes) are very bigge, both for the

grape and the cluster, sweet and good." In what is now Dorchester, Wood

said there was "very good arable ground, and hay grounds, faire

corne-fields, and pleasant gardens with Kitchin-gardens." Boston, he

pointed out, was blessed by "sweet and pleasant Springs" ... which as

may be noted, was the very reason that John Winthrop and his associates chose

the site for settlement after a failure across the Charles River at what is now

Charlestown.

Yet another interesting account of colonial days is that of

John Josselyn, published in 1675. In his book New England Rarities, which is

hardly noteworthy for its restraint, John has much to say about apples and

cider; for example," ... I have observed with admiration that the (apple)

Kernels sown or the succors planted produce as fair & good fruit without

grafting as the tree from whence they were taken; the Countrey is replenished

with faire and large orchards. It was affirmed by one Mr. Wolcutt (a magistrate

established in Connecticut after leaving Boston) that he made five hundred

hogsheads of syder out of his own Orchard in One year. Syder is very plentiful

in the Countrey, ordinarily sold for Ten Shillings a Hogshead. At the

tap-houses in Boston I have had an Ale-quarter spiced and sweeted with Sugar

for a Groat .... The Quinces, Cherries, Damsons set the Dames at work.

Marmalade and preserved Damsons is to be met with in every house. . .. I made

Cherry wine, and so many others, for there are a good store of them both red

and black. ... "

In passing, it may also be noted that the colonists planted

many pear trees, not only as a table fruit in season but also as a means of

making a pear-cider, commonly known as perry. On the very best authority, the

reader may be assured that perry when properly aged can give a most gratifying

result for the moment, although gastrically it is worse than even very hard cider.

The colonists were devoted to their fruit trees, perhaps

feeling that the familiar fruits of home were an establishment of civilization

in the wilderness. Indeed, it has been said that the church bell and the apple

tree crossed America hand and hand as the tide of settlement moved westward.

William Blackstone, who lived near what is now Boston Common on the side of

Beacon Hill, had an apple orchard well established before the Puritans

8

came in 1630. John Winthrop hastened to plant his island off shore (Governor's

Island) with a garden in which apple and other fruits were set out. Out in

present Roxbury, Justice Paul Dudley planted a garden in which he reported, he

grew eight hundred peaches upon a single tree and that he grew pears "eight

inches around the bulge." Gardens, very much in the English style, became

common in Boston proper, once the colonists were firmly established, and caused

visitors who expected sod-covered huts of logs to greet them, to write with

astonishment of the beauty and prosperity of the infant colony. Governor

Bellingham built a garden along what is now Tremont Street and here he reared

the very first "greenhouse" in America. Thomas Hancock had a

"magnificent plantation" on the site of the present State House. One

other well-known early garden was located in the present South End where Perrin

May had a "famous orchard." His fruits were of tremendous size but

uncharitable neighbors said this unexampled fertility was due to the fact that

May trapped house cats and used one at least at the base of each tree for

fertilizer. May, however, was probably one of the first to make use of sea

weed, such as kelp for fertilizer; that material sounds better for plant food

than pussy cats.

While many other references could be listed, these will

show how pleased the settlers were with the Boston area and we can infer that

Deane Winthrop and a few other settlers in Winthrop itself experienced the same

good fortune. Certainly there is no reason to suppose that Winthrop was any

different from the adjacent territory and crops must have flourished here as

easily and as prosperously.

From these early accounts, it would seem that the abundance

of wild life was even more remarkable. General Benjamin Butler, that

unfortunate man more celebrated for his acid tongue than for his many

accomplishments and services once remarked that the storied hardships of the

first settlers were largely imaginary for there was so much wild life about in

the woods and on the beaches, as well as in the sea and the rivers, that they

could have starved only if they were lazy enough to fail to pick up what was

lavishly laid out before them.

Deer were certainly very abundant. Indeed a quotation from

William Wood's New England's Prospect, probably written about 1634, makes this

dear, while at the same time explaining how Deer Island and Pullin Point,

Winthrop's first name, were so called.

"The last Towne in the still Bay (Boston Harbor) is

Winnisimmet (variously spelled); a very sweet place for habitation and stands

very commodiously, being fit to entertain more planters than are yet seated; it

is within a mile of Charles

9

Towne, the river (Mystic) only parting them. The chief islands which keepe out

the winde and the sea from disturbing the harbours are, first Deare Island,

which lies within a flight shot of Pullin Point.

"This Island is so called because of the deare which

often swimme thither from the maine, when they are chased by wolves. Some have

killed sixteen deare a day upon this island. The opposite shore (across Shirley

Gut) is called Pullin Pointe, because that is the usual channell Boats use to

passe threw into the bay (Boston harbor); and the tide being very stronge, they

are constrayned to goe ashore and hale their boats, by the sealing, or roades,

whereupon it was called Pullin Point. ... "

Perhaps it should be noted that spelling was a matter of

somewhat individual whimsey in those old days, at least at the hands of the

Puritans and their associates. Few men could read or write well; many could not

do either at all. When a man was actually compelled to write, it was a task of

considerable labor, not merely because it was unaccustomed work, but because

the author, while he might have a fairly good oral vocabulary, had only a

general idea of how the words he used should be spelled. So, when he came to a

word he did not really know, he was apt to spell it as it sounded to him. Thus

much of the old writing is somewhat original. Then too, these writers made use

of many words which have since been lost and forgotten save by scholars.

Next to deer, perhaps a major game source was the wild

turkey. These were big birds and very delicious. Then, they were abundant in

and about Boston. At a single shot a man or boy could bring home 20 pounds or

so of the most highly prized meat. Wood wrote, in 1634, " ... forty, three

score, and even a hundred in a flock ... There have been seen a thousand in one

day ... " Characteristically, the settlers did not value what was so

plentiful and Josselyn in 1672, about fifty years later, wrote " ... the

English ... having so destroyed the breed that it is very rare to meet a turkey

in the woods." Of course, today, the wild turkey is unknown in all New

England.

Just as the settlers exterminated the turkeys, so they were

profligate with other game. Deer very soon became scarce; bear were nearly

exterminated, save in the depths of the Maine woods. Probably the greatest

waste of all was in wild birds.

The passenger pigeons are a classic example. Today, not one

is known to be alive anywhere. When the settlers came, reports Wood, there were

"millions and millions." Indeed, many later writers in other parts of

the country where hunter's guns were just beginning to roar, reported that the

earth was literally shadowed as by a cloud when a flock of pigeons passed overhead.

Other writers speak of vast areas of the forest which were

10

swarming with the birds to such an extent that the ground was soiled inches

deep for hundreds of acres while the noise of the birds was that "of a

rushing river tumbling over a rapids". It is even reported that the birds,

who were certainly gregarious, nestled so closely together and in such

numbers, that their combined weight stripped giant oaks and maples of their

larger boughs. These pigeons were shot, netted and trapped and so squandered

that within a few years, as civilization moved westward, they were literally

wiped out of existence.

The importance of wild fowl as a source of food was made

evident in 1632, just two years after settlement, when the General Court ordered,

"That noe person whosoever shall shoote att fowle upon Pullin Point

(Winthrop) or Noddles Island (East Boston), but said places shall be preserved

for Jobe Perkins to take fowle with netts."

No one in New England at least, now practices the ancient

art of fowling but it is one of the oldest of arts, being described in the

Middle Ages as an "ancient and honorable mystery." Boys were

apprenticed to master fowlers and thus learned the profession. Primarily it

consists of taking birds alive by means of nets, snares and various devices

such as bird-lime -- which last consisted of smearing the branches where birds

roosted in numbers at night with a sticky paste which held them fast until

morning when the fowler picked them off like fruit from a laden apple bough.

Certainly few fowlers ever had a more luxuriant opportunity

than Jobe Perkins at Pullin Pointe and Noddles Island. The section then was

heavily wooded, the beaches were numerous and there were the great unspoiled

salt marshes -- ideal attractions for many kinds of birds. What is now Belle Isle

Inlet -- what is left of it -- was then a much deeper tidal estuary winding

between the salt marsh grasses. Although no description of Perkins' work

remains, it is to be imagined that he built a frame work of light saplings for

several hundred yards along and over the creek. This frame work was wide at

the open end and narrowed down to a very small diameter at the farther end.

Perkins and his aides would wait until there was a considerable flock of birds,

say at about where the present Winthrop-East Boston bridge is now and then, in

row-boats, drive the birds into the net and force them deeper and deeper into

its constrictive diameter until, at the end, they could pick up the birds by

hand -- taking them alive to Boston market.

What happened to Perkins' concession, how much he paid for

it and similar questions cannot be answered, but certainly Winthrop's first

fowler had unlimited stock.

Back in those days, before the wasteful habits of the

settlers

11

could make any serious depletion of wild life noticeable, the marsh and forests

teemed with birds. Winthrop, its woods, fields and beaches, was a nursery for

multitudes of birds. Indeed, on the ledges and sands of the outer beach, the

great auk, now extinct, and such other birds as the gannet, shag, cormorant,

puffin and many kinds of gulls and terns, not to mention many more lesser birds

were at home. The wildness of the Winthrop beaches and rocks can be attested by

the fact that they were also home to such animals as walrus and various types

of seals. It was a hunter's paradise indeed.

Here too were seen in considerable numbers the white swan,

the sand hill crane, the heron, the brant, snow geese, Canada geese and such

ducks as mallards, canvas backs, eider, teals, widgeons, sheldrakes and many

others. Most of these commonly bred in Winthrop then, although of course the

great breeding grounds then as now, were to the north. Yet each Spring and

Fall, during the migrations, the sky was filled with clouds of these birds and

Winthrop's marshes often sheltered countless thousands of them at night.

It must have been a magnificent sight then, to go out in

the early morning, or late in the twilight, to see and hear the geese and duck

in their hosts. How they must have deafened the ear with their clamorous

calling and the beating of their wings must have sounded like constantly

rolling thunder. Morton reported in 1642, "I have often had a thousand

(geese) at the end of my gun."

Plover and the smaller birds, such as sandpipers and the

like, were so numerous and so small as to be hardly fair game. Yet they, with

the passenger pigeons previously mentioned, were often taken and used in making

pies -- which was a sort of massive dish consisting of several pounds of bird

flesh baked between thick layers of biscuit -- like crust in a lordly dish.

This was a hearty meal and may be relished today, in a dwarfed and pale copy,

in our modern chicken pie.

These smaller birds were very easy to kill, although many

hunters regretted wasting "their shotte upon such small fowles."

Morton reports " ... sanderlings are easier to come by; because I must go

but a step or two for them. I have killed between foure and five dozen at a

shoote, which would load me downe." There were larger plover, known then,

and the names are still heard amongst old timers, as "humilities" and

"simplicities." Says Wood again, "Such is the simplicitie of

these smaller birds that one may drive them on a heape, like so mannie sheep,

and seeing a fitte time, shoote them. The living, seeing the dead, settle

themselves in the same place againe, I myself, have killed twelve score (240)

att two shotts."

12

Of course birds were far from being the most important source of wild food.

Deer was probably the great food staple. When the Puritans came the woods of

Winthrop were teeming with the gentle animals as the name Deer Island attests

but the animals were very soon exterminated and from then on, the only deer

that came into Winthrop were refugees from the still unspoiled forests of what

are now Saugus, North Revere and Malden. Soon these forests were emptied also

and that was the end of deer in our section.

The moose was commonly seen in Winthrop too, in the early days,

but this huge creature, larger than a horse, very soon vanished at the end of

the settler's guns. There were elk and caribou also, in very limited numbers

probably, and they did not long satisfy the settlers' hunger for meat because

they are creatures of the wilderness -- even more so than the moose. Of the

four animals the deer alone has managed to survive in numbers in New England.

Indeed, it is said that there are more deer in New England today than there

were when the settlers came. The reason is, of course, that the deer is

comparatively small, very agile, and has managed to adapt himself to feeding on

the fringes of the farm. Any hunter will tell you that deer in open, that is farming

country, are much larger than the forest deer as for instance in the depths of

the Maine woods.

There were many small animals in Winthrop at the beginning

and these managed to survive longer than did the bigger creatures. Such were

rabbits, squirrels and raccoons. The first was used for meat after the deer

vanished, the raccoon was exterminated for its fur but the squirrel remained

and still remains because he is of no value for either fur or food. Of course

in Winthrop today, with practically every inch occupied by houses there is no

possibility of any wild animal, save mice and rats and squirrels existing. What

is left of the marshes and the outer beach still provides resting places for

migrating water fowl hut the glory of wild life that once made Winthrop noted

has vanished.

Fish took the place of game as a source of food as the

larger wild animals. were destroyed. And for many years, Winthrop was a

splendid place for fish and for sea-food; it was not until contemporary times

that the pollution of the harbor ended this.

A mere catalog of the fish that have been and still are

caught off Winthrop shores, though seldom now in the harbor exemplifies this

sea-given wealth of the town: bluefish, bream; catfish, cod, dogfish, eels,

hake, flounders, haddock, herring, mackerel, mackerel shark (one typical of

several small species), perch, pollock, porgy, sculpin, shrimp, skate, smelt,

tuna, tautog and many more. As for shellfish, oysters once abounded; they

13

soon vanished. For many years, these have remained: clams, crabs, lobsters,

quahogs, scallops, sea clams and many more less edible species. Of small

interest now but formerly valuable for oil, were such as whales, porpoises and

blackfish.

A catalog of wild animals of Winthrop, made by the late

George McNeil, includes such as: bats, chipmunks, field mice, fox, gray

squirrel, red squirrel, mink, moles, muskrat, rabbit, rat, skunk, weasel,

woodchuck-plus of course the old deer, moose, elk and caribou. As for snakes

Winthrop now has a very few harmless ones, such as blacksnakes, green snakes,

garter snakes and possibly a few more but in the beginning, Winthrop had

various slightly poisonous adders, such as the striped adder and the house

adder while, sad to say, the virulent rattlesnake was once a nuisance, although

scarcely a peril. The poisonous snakes were quickly killed and none have been

reliably reported for the past century.

Geologically, Winthrop is part of the general New England

region which is one of the oldest, that is unchanged, portions of the earth's

crust. Geologically, the basis of Winthrop runs back many millions of years,

being part of the Appalachians, the mountains which are the mere stumps of what

were once lordly peaks five miles high or more. Specifically, the New England

Acadian Section, is Pre-cambrian and elder Paleozoic in character. Many ages

ago, the rocks were crushed and folded like paper in a mountain building

process. Up through the shattered rock then poured rivers of igneous rock

which, however, seldom broke through the then existing surface. These

"domes" or intrusions cooled in place and, when subsequently

uncovered by erosion and glacial action, comprise the present day granite so

characteristic of much of New England.

Since the mountain building, there have followed uncounted

years and ages of erosion of various types. At least a mile-thick layer of

surface has been removed in the process, much more of course from the higher

elevations. Thus the original snow-capped mountains were ground off and washed

away to mere hills, or even obliterated. Much of New England became a flattish

peneplain -- known as the Cretaceous peneplain for its being formed in that

period. Much of New England during the time was sunk beneath the ocean.

Next followed another period of stress and strain and New

England was crumpled upward again. Volcanoes erupted, lava flowed and, when the

motion ceased, most of New England was lifted bodily perhaps 2,000 feet with

the worn away mountains once more respectably high. Oddly enough this uplift was

not equal but was highest in what is now Vermont and lowest in

14

what is now the Cape Cod area. Thus all New England was

tilted from northwest to southeast.

Once again followed another long period of erosion. Rivers

carved themselves new valleys and, along shore, the ocean pounded rock to sand

and built great beaches. This period was that of the Tertiary and the resulting

peneplain is known by that name. It came to an end with a very slight upheaval

which served to elevate the north west and broaden the lower reaches near the Ocean.

Perhaps, as a very general statement, the shore line then was an average of 100

miles farther to the east. It was a remarkable shore line, especially along the

southeastern Massachusetts coast. Several now placid rivers, like the Charles,

tore great canyons in the rock near the ocean, making gorges as great as those of

the present Grand Canyon of the Colorado. These gorges still remain -- under

the ocean.

It was during this period that the sea alternately invaded

the shore and then retreated, over swings of thousands of years. The present

period is one in which the ocean is sweeping in and this has given us the

characteristic drowned valley type of coast. Rivers have been shortened and the

salt water has entered into their valleys making tidal estuaries. As the land

subsided, high spots on ridges would remain above water, making numerous

islands, often connected one with another and with the mainland by a higher

ridge, thus forming peninsulas.

Of course much of this outlined geological history is

necessarily obscure since nearly all of its features have been obliterated by

glaciation. It is to glaciers that Winthrop owes its form and character.

This planet of ours has experienced several "ice

ages," perhaps seven, so far. When the world went into one of these cold

periods, sheets of ice, sometimes a mile in thickness, would creep down out of

the north and in their coming -- as well as in their departure, when the

climate warmed again -- they profoundly changed the face of things.

The last glacier, which created Winthrop and its vicinity,

came during the Pleistocene age and receded from here something like 25,000

years ago. This great ice sheet, which apparently originated in the Laurentian

region to the north and north-west, moved slowly, very slowly, in a

northwest-southeast direction.

It overwhelmed everything in its path. Tops of mountains

were sheared off, loose rock, soil and sand picked up and carried along -- as

snow from the edge of a plow. The mass of rock at its forefront acted like the

cutting blade of a titanic bulldozer and cut off the topsoil and the 'hills and

pushed the mass ahead of itself.

15

Even more, the ice changed the shape of the mountain masses it could not level.

As it climbed up the northwest side of the hills, the cutting edge created a

long smooth slope. At the top, the final several hundred or thousand feet was

sheared away. Then, as the ice sheet tumbled down the southeast side of the

mountains, it fell so easily that the side remained steep. Indeed, if the

southeast angle is projected upwards, and a similar angle projected from the

base on the northwest side, it is demonstrated that the point where the lines

intersect indicate the original height of the mountains. What are now a

thousand or two feet high, were once mountains four and five thousand feet

high. New England was once as lordly mountainous as Switzerland -- long ago.

The Alps are very young as mountains go. Eventually they too will be worn to

stumps but by then New England may grow a new crop of snow-covered peaks.

Finally, when, after many years, the ice edge reached about

as far as present New York City, the climate turned warmer. The ice halted and

then began to retreat; which is to say, the ice melted away.

No living being can image the terrific confusion the ice

left behind as inch by inch it retreated hack into Canada. Streams of water

gushed across and out from under the ice in massive torrents. This was the

tool, these vast masses of swiftly rushing water, which carved New England into

what is, more or less, its present face. You see, as the ice halted, it left at

a standstill the masses of rock and sand, clay and loam, which it had carried

along as it moved south. This it promptly deposited, forming what is known as

the terminal moraine at its southeasterly edge and its lateral moraine at its

easterly edge. According to some geologists, this terminal moraine formed Cape

Cod and Martha's Vineyard and Nantucket -- for example.

The melted ice rushing through and over these moraines

shaped them into outwash plains, kames and eskers. In places the ice water

washed the moraine completely away; in others it shaped the mass into domes and

hills with valleys between. Just as the wind after a snow storm drifts the soft

snow into weird shapes in an hour, so through many years the water shaped the

moraines into various forms. Of course, the process thus begun has continued

ever since for wind, rain, frost and sun constantly erode the face of the earth

-- tearing it down and preparing for another age of mountain building, perhaps

a million years from now, perhaps tonight. New England is staid and quiet geologically

now; but it may erupt into fire and flame at any moment as the rock beneath our

feet awakens once again. The hills may seem eternal but to the geologist, a

thousand years is but the tick of the second hand on a clock.

16

So far as Winthrop is concerned, when the ice sheet retreated from here, it

created all our hills. These are a very peculiar type of formation-for, while

most hills are at least in part masses of rock, our hills are made up of sand,

pebbles, small boulders and clay -- "unconsolidated till" is the

technical name, meaning loose soil.

These hills are known as drumlins. They were not forgotten

by the retreat of the glacier at the end of the ice age but were made during

the ice age itself when, as the climate fluctuated, the glacier's edge

alternately advanced and retreated over short distances -- perhaps a few

hundred feet rather than several hundred miles as in the general advance and

final retreat.

Take a piece of bread, a small piece, and roll it lightly

back and forth on the table. The bread will form a sort of thick and pointed

cigar. That is how drumlins were made. The glacier rolled back and forth

beneath its edge great heaps of debris and thus what now resembles half

footballs resulted.

Winthrop's hills are all drumlins, so are the hills of

Revere, East Boston and Chelsea. So are many of the Islands in the harbor -- what

is left of them. Specifically, Deer Island, Great Brewster, Long Island and the

now vanished Apple and Governor's Island were all drumlins. So is Point

Shirley, Great Head and the four hills at the Highlands with a smaller group or

pair of the drumlins making up the Center and Court Park sections.

Of course, time and the ocean have not dealt kindly with

the drumlins. Being soft as compared with rock, they have been greatly eroded.

An example of erosion has been the cut of Highway C 1 through the western end

of the drumlin which is Orient Heights. This cut was originally wide enough

only to keep the sides in permanent shape but rain washed away the soil until

the road below was badly mudded over on the east side. Not until the bare soil

was sodded over was this erosion stopped.

As the ice went away, the bare drumlins, until grass

covered them and checked wind and rain erosion, washed down filling the space

between the hills. Thus the salt marsh between Winthrop and Beachmont and

between Winthrop and East Boston and Revere was brought into being. Drainage of

tidal waters formed Belle Isle Inlet and its "tributaries." Indeed,

until the marshes were recently choked with debris from the airport and the

pumping of mud to form the oil farm and Suffolk Downs, the marshes were in

miniature a complete river basin, save that the current alternately flowed in

and out. Then the marshes open to the sea were closed away by the formation of

what is known as barrier beaches and the placid marsh was allowed to build

itself up to high water level, by means of silting with humus formed by the

annual decay of the marsh grasses and weeds. A cross section

17

of these marshes gives a complete description of the geology of the past 25,000

years or so for the different layers of silt, sand, blue clay down to the bed

rock far below to a geologist are as complete a history as if it had been

written and published by man.

Probably the greatest agent which affected the drumlins was

the ocean. The waves, especially during storms, battered them and ate

mercilessly away at their substance. Orient Heights, protected by its marshes,

is a good illustration of a drumlin which has not been much damaged by erosion.

Only man has corroded its majesty. Great Head is a good example of a drumlin of

which the ocean has destroyed about half of its length. Cherry Island bar, off

Beachmont, is an example of a drumlin which has been completely leveled by the

waves. Of course, Apple Island and Governors Island are examples of drumlins

leveled by man -- the Airport consumed their substance.

As the ocean chewed away at exposed drumlins, the water

carried away the sand and clay and the smaller pebbles while the larger

boulders dropped down and were actually built into a sort of breakwater which

gave some measure of protection against the waves. Of course, it was not

adequate protection and hence in modern times we have been compelled to build

sea walls along the shore front from Revere Beach, past Beachmont, around the

Highlands and right down to Point Shirley. The damage winter northeasters

sometimes do to even these modern sea walls, shows that we have reined back,

not entirely halted the ocean. However, if the walls had not been built, it is

altogether likely that Beachmont Hill, the Highlands and Point Shirley would

all have been washed away -- as indeed they may be yet, unless we keep the sea

walls in constant repair.

These rocks formed reefs which alter tidal and storm currents

so that the sand and small pebbles washed out are deposited along between the

drumlins. Thus our beaches came into being, composed of the ruins of the

drumlins between the reefs -- as between the end of Beachmont and the

Highlands, between the Highlands and Great Head and between Great Head and

Point Shirley. As breakwaters and sea walls are built, the currents are altered

still further. Thus in some places the beaches are being lowered and in others

built higher. For example, the beach along the Crest, between the Highlands and

Cottage Hill, has been notably elevated in the past few years since the

breakwater was built off shore. Probably, within a few more years, what was the

area of water between the shore and the breakwater will be filled in and

Winthrop Beach will be that much wider. This formation

18

of reefs and beaches is a continued process. Every storm makes changes; and

every change has its consequences. Undoubtedly we can keep the present area of

Winthrop, and perhaps even persuade the ocean to enlarge it rather than wear

the shore line away. However, it must be remembered that this will only be so

if constant vigilance is maintained and the walls and breakwaters kept in

repair.

These drumlins, when the Puritans arrived must have been

very attractive, especially to sea-weary eyes. The hills stood up out of the

levels of the salt marsh, not bare and shabby as we know them now, but clothed

in heavy forests, probably of white pine, oak, birch and maple. This forest

cover gave the soil protection against erosion and thus the hills had

accumulated through the many centuries a rich and fertile humus. The subsoil,

being of unconsolidated till, was "tight" and thus the food elements

put into the soil by the forest did not leach away -- as it does in sandy and

loose soils. The Indians, of course, had cleared little areas here and there by

fire for their corn but they were not farmers. They much preferred to live by

hunting and fishing and hence while they did plant corn, beans and pumpkins,

they did not "farm" in the sense that large, cleared areas were

utilized.

The scene is so different now, with buildings, many of them

not designed to be attractive, covering all the drumlins, with roads cutting

through the hills, with ugly skeletons of electric wire poles strung everywhere

-- and with every forest tree cut down long since, that we descendants of the

Puritans cannot realize how the town and its neighborhood did look 330 years

ago. Mellen Chamberlain in his History of Chelsea visualized the aspect of his

town by writing: "While the bold bluffs of Winnisimmet were untouched by

the leveling hand of man, and the great hills of the main, toward the north,

and the lesser heights to the east, south and west, stood at their original

elevations, and covered with primitive forests, the situation must have been

one of scarcely paralleled beauty and interest."

Channing Howard, Winthrop engineer for many years, has

written the following description of our town: "Here was bold bluff and

sandy beach along the outer shore against which lapped the never still waters

of the open sea, and the broad expanse of salt meadows and placid winding

creeks in the distance, and the hills of varying height in our own territory, and

the higher hills to the north ... Bordering us by the south and west lay

splendid waterways for future commerce ... all kinds of landscape which the

heart could wish, either for the eye of beauty or for the most

19

utilitarian of purposes, except the proverbial New England babbling brook and a

rock bound coast. Neither of these exists, or did exist in our borders."

Of course, under this original beauty and wealth of forest

and game, some colonists found things they did not like too well. Their comments

are particularly illuminating, both in reference to geography and to wild life,

previously described.

One of the original settlers of the Puritan colony at

Charlestown, was Anne Pollard, who died in 1725 at the age of 105. She claimed

she "was the first to jump ashore" from the Winthrop party in the

passage from Charlestown to Boston in 1630 and afterwards said she remembered

the site of the future city as being "very uneven, abounding with small

hollows and swamps, and covered with blueberry and other bushes."

The same thickets were described by Captain Edward Johnson,

writing about 1640. He said that "At their first landing the hideous

thickets in this place were such that wolves and bears nurse up their young

from the eyes of all beholders."

The section was famous for its good springs and clear,

sweet water. The Indian name for Charlestown, Mishawum, means "a great

spring" while Boston's Indian name, Shawmut, means "living

fountain." There was indeed a great spring near Blackstone's house at

about the present locality of Louisburg Square while there was "the great

Spring" in Spring Lane, a little alley now running down from Washington

Street just parallel with Water Street to the United States Post Office

Building. When the foundations of the new Post Office building were put into

place, the engineers were reported to have had some trouble with the waters of

this spring -- which were still flowing under the buildings and pavements of

modern Boston.

Wood had much to say about water in the Boston section.

Writing in 1634, he remarked: " ... for the countrey it is as well watered

as any land under the Sunne, every family, or every two families having a

spring of sweet waters betwixt them.: which is farre different from the waters

of England, being not so sharpe, but of a fatter substance, ... : it is thought

there can be no better water in the world, yet dare I not preferre it before

good Beere, as some have done, but any man will choose it before bad Beere,

Wheay or Buttermilk. Those that drink it (Boston's spring water) be as

healthfull, fresh, and lustie, as they that drinke Beere; these springs be not

onely within land, but likewise bordering upon the sea coasts, so that some

times the tides overflow some of them ... "

Wood was much interested in the trees comprising the

forests in the vicinity of Boston, including Winthrop by inference. Indeed, he

wrote the following verses about the local trees:

20

"Trees both in hills and plaines, in plenty be,

The long liv'd oake, and

mournful Cypris tree,

Skie towring pines, and Chestnuts coated rough,

The

lasting Cedar, with the Walnut tough;

The rozzin dripping Firre for masts in

use,

The boatmen seeke for Oares light, neate grown Sprewse,

The brittle Ashe,

the ever trembling Aspes,

The broad-spread Elme, whose concave harbours waspes,

The water-spungie Alder, good for nought,

Smalle Elderne by th' Indian Fletchers

sought,

The knottie Maple, pallid Birtch, Hawthornes,

The Horne bound tree that

to be cloven scornes;

Within this Indian Orchard fruites be some,

The ruddie

Cherrie, and tee jettie Plumbe,

Snake-muthering Hazell, with sweet Saxaphrage,

Who

spurnes in Beere allayes hot fevers' rage.

The Diars Shummach, with more trees

there be,

That are both good to use, and rare to see."

To conclude this chapter, somewhat out of chronological

development, it should be pointed out that Winthrop, although almost in the

shadow of the State House, and more or less a part of Boston until 1852, was

actually rather remote from the future city for some 200 years.

The two islands which are now East Boston, were never part

of Winthrop or of any interest to Winthrop people. Actually Winthrop was tied

to Revere as a pensinsula, and Beachmont and adjacent Revere, another

peninsula, was tied to Chelsea, and Chelsea itself was also a peninsula,

reaching Boston by means of a ferry over the Mystic and Charles rivers.

Chelsea, Revere and Winthrop, a series of three peninsulas, extended to the

east and north of Boston but was sharply cut off from Boston by estuaries.

The natural way of Winthrop people to go into Boston was,

of course, by water -- row boats and sailing boats afforded the most rapid and

the easiest way to town. There was considerable need of visiting Boston, too,

for Winthrop was in the beginning and ever since has been dependent upon the

City. Today, to drive to Boston, we go over the Belle Isle Creek bridge to

Orient Heights and thence the length of East Boston and into the city through

the Sumner Tunnel. There was no bridge over Belle Isle Creek until 1839. Of

interest is also the fact that the road across the marsh between Orient

Heights and Beachmont, was not built until 1870, while the road which gave a

direct route from Chelsea to Revere was not constructed until 1802.

Boats served passengers and small loads of freight between

21

Winthrop and Boston, or Revere, or Chelsea, but the moving of heavy loads was

difficult. For example, previous to the Revolution, if a Winthrop farmer, and

all Winthrop people were farmers then, wanted to take a load of hay or a dozen

beef cattle into market, he could drive only by a very roundabout way.

He would leave Winthrop by what is now Revere Street and

pass along the eastern and northerly side of Beachmont to what is now Crescent

Beach, Revere. Then he would go up Beach Street to what was then Chelsea

Center, then over into Malden, to Medford via Everett, across the Mystic River

into Somerville and on into Cambridge. Crossing the Charles near Harvard

Square, he would finally arrive in what is now Brookline and then, turning east

again, go through Roxbury and so into Boston by way of Roxbury Neck. This was

described in the writing of the day to be about fourteen miles although today

it would seem to be a much longer trip. In contrast, a sailing boat with a fair

wind could make the trip in under an hour while a row boat could certainly

reach Boston from Winthrop in an hour.

This roundabout travel continued for perhaps a century because

Winthrop and Revere were very small, farming sections. During these hundred

years, many changes took place. The forests were wiped out. The soil was placed

under cultivation -- although with the primitive tools, with only horse and

oxen to do what man's awn muscles did not, agriculture was exceedingly

primitive. At about 1711, for example, a carefully made map located only four

houses in Winthrop, one in Beachmont, two in other parts of Revere and four on

the water's edge in Chelsea.

To serve the needs of these farms, several roads were laid

out. These roads are not to be thought of as being real roads in the modern

sense of a paved highway over which automotive vehicles roll at 40 to 50 miles

an hour -- when the police are not around. These roads were mere dirt tracks,

hub-deep in mud in the Spring, dusty in hot weather and frozen tangles of ruts

in Winter. Indeed, farmers used these roads as little as possible, save in

Winter, when snow covered the roughness. All heavy moving possible was held

until snows were deep and over the smooth surface sleds skidded more easily

than at any time of year. Actually, the first roads were just rutted tracks

which were called roads because they were rights of way and because the more

objectionable stumps and rocks were removed.

Until bridges were built, these roads were primarily fixed

by running from one fordable place in a stream to the next. They avoided the

steepest grades and made detours often a long way around to make their way

across the marshes. As for foot travelers, almost everybody walked, or else

rode horseback -- for to ride in the huge-wheeled carts over the rough surface

of the

22

roads was sheer torture. Of course, it must always be remembered that Winthrop

people commonly went to and from Boston by water -- safe, swift and easy.

Winthrop people even went to church by boat, sailing up Belle Isle Inlet and

down what is now the upper part of Boston harbor, near the present oil farm

wharves and the gas tanks to as near Beach Street as possible. It was there, on

Beach Street, near the present corner of School Street, behind the Library and

the High School, that the First Church was built in 1710. Before that when

Winthrop went to Church, services were either held in private homes, or else

people sailed across the harbor to the churches at Boston itself -- about as

near as the old Chelsea Church. This Rumney Marsh Church, which became

Unitarian, is still standing, although somewhat reconstructed during its 250

years. It is the present home of Seaview Lodge, Ancient Free and Accepted

Masons.

As Boston grew, and other towns, particularly to the south,

as Plymouth, Taunton and the like developed, and as other towns, as Framingham

and Worcester to the west, and Lynn, Salem and Newburyport to the north developed,

the problem of land transportation became acute. Mails had to be carried and

passengers clamored for stage coaches. Thus, of particular interest to Winthrop,

the old Salem Turnpike was built -- probably the first real road in what is now

the United States.

This pike ran from the Winnisimmet Ferry over the Mystic, between

Charlestown and Chelsea to Salem. Basically, it was an old Indian trail, as

indeed most of the early highways in New England were. The settlers used these

trails and as such they served well enough for men and women on foot or on

horse-back -- but of course no wheeled vehicle could roll over them until they

were widened and smoothed. The Old Salem Turnpike which has been considerably

moved about since the early days, was picked out a number of years ago by

Channing Howard of Winthrop and Mellen Chamberlain of Chelsea.

"Starting at the old ferry site, this road continued

past the old ferry tavern (Taverns were an integral part of travel in the 18th

Century) eastward by the Shurtleff farm mansion house, along what is now

Hawthorn Street, up the present line of Washington Avenue, around Slade's

Corner where the Carter farm mansion stood, and where the road leading to

Medford and Cambridge branches to the west (now County Road) and on to Sagamore

Hill, now known as Mount Washington, past the Pratt House and thence through to

North Revere, Cliftondale, Saugus, and Lynn to Salem. When the road across

the Lynn marsh was built, the Salem pike was relocated to go across Chelsea,

probably what is now Broadway, straight down Broadway, Revere and so into Lynn.

This saved many miles. Today the highway of

23

Route One, skips through the rear of Orient Heights, slides across Revere to

cross the old pike at right angles and so to North Revere, Saugus and Danvers

to the North." To reach Revere, Salem and even Newburyport, it is now

necessary to turn right off the highway. In the old days, highways were built

to connect towns; now they are built to avoid towns.

The first road in Winthrop of which there is any official

record (probably the officials merely recognized an existing fact, when they

got around to it) came in 1693 when the Selectmen of Boston, "Iaid

out" a road which began at "Bill Tewksbury's gate" (there are

many spellings of the name Tewksbury) at Pullin Point, along the shore by

Beachmont to Crescent Beach and thence, turning left, up Beach Street, Revere,

to the Chelsea church where it joined the Boston and Salem road.

By the time the Revolution came, this was about the physical

condition of Winthrop, Revere and Chelsea. Men used the roundabout roads when

they had to do so; otherwise they sailed or rowed boats. This may seem strange,

because Boston in 1775 was the largest and most prosperous city in the

colonies. The reason is that Winthrop, and to a minor degree less, Chelsea and

Revere, were still farming communities -- actually one town.

In the early part of the 19th Century, Chelsea had grown

and, as a separate town had its center with a town hall and a church at what is

now Revere Center. A bridge was built across the Charles between Charlestown

and Boston in 1785 -- before that the only way to leave Boston by land was out

Roxbury Neck. Then when the Boston-Salem turnpike was built in 1802, a bridge

was built over the Mystic between Charlestown and Chelsea. These conveniences

to travel north and east resulted in a great development for Revere and Chelsea

but Winthrop, being way out farther to the east was still aside from the stream

of travel and commerce and hence drowsed along until almost the end of the 19th

century as a peaceful farming community. The growth of Chelsea and Revere was

so great that in 1846, Chelsea consented to Revere splitting away. Winthrop, of

course went with Revere, a sort of tail to the dog.

At mid-century, just a hundred years ago, the third great

geographical change was accomplished, Winthrop people, who had by then

increased in number, began to chafe under the rule of Revere. Revere, for its

part, was not at all concerned with the square mile of marsh and drumlins which

was Winthrop and so, in 1852, Winthrop was established as the present town -- a

separation which recent years have proved to be an excellent thing.

Winthrop at that time was still primarily agricultural.

From time to time there had been attempts to establish industry

24

but all failed. sooner or later and Winthrop has remained practically

industryless. From most points of view this has proved to be good -- for it has

prevented the town from suffering the various evils and discomforts of

industrial concentration. Economically, of course, there are disadvantages but

on the whole Winthrop is very fortunate to be a town of homes alone.

Being so near Boston, Winthrop could not long continue to remain

agricultural. Land increased in value to a point where it could not be

profitably farmed. Outside pressure became so great that an opportunity

developed for the division of the farms, and the subdivisions of the divisions

so that almost every square foot of land, town property and marshes aside,

became a house lot. There are few towns which are so thoroughly well built up

as Winthrop is today -- just as there is no area of comparable charm so easily

accessible to Boston.

The development of Winthrop out of farms to homes was made

possible, by the establishment of transportation. Steamers plied for a time

between the town and the city, but primarily it was the railroad which made the

town's metamorphosis directly possible. Today the rails have been torn up and

private cars and the bus line, feeding the Rapid Transit system at Orient

Heights carry the load. Few communities are so thoroughly emptied of mornings

and so filled up again at night in two brief peak loads as is Winthrop. But

transportation is a story for a subsequent chapter.

25

----------------- Top

Chapter Two

THE INDIANS

MUCH of the modern, popular idea of the Indian stems from

the idealized and imaginative figures created by the motion pictures. The

Indian actually was very far from a noble savage. Judged by white standards,

the redskin was mean, cruel, dirty and -- in short, vermin. The old saying,

"The only good Indian is a dead Indian" was a judgment based upon

experience.

There can be no doubt that, according to their own lights,

the Indians were justified in attempting to retaliate upon the white settlers.

Any man worth his salt would fight by whatever means possible to save his home,

his family and himself from brutalization and exile. No critic of the Indian,

however bitter, would deny that the Indian was a first-class fighting man.

The trouble was that the Indian culture was so different

from the European that the two could not exist side by side. On one ground

alone, economic, this is abundantly clear. The Indians were primarily hunters.

To subsist as such, a hunting culture requires comparatively vast areas of

forest and water. The European culture was basically agricultural; a few acres

would support a person. Thus New England could support a multitude more

Englishmen than it could Indians. Now, to practice agriculture, it is necessary

to destroy the forest cover, to allow the sun to strike in upon the soil. A

hunting culture requires the forest be undisturbed. So -- conflict was

inevitable and, given the superior weapons and social organization of the

English, the result was inevitable. The Indian had to go. The manner of going

can be criticised as having been far too brutal and bloody but sentimentalists

of the 20th Century do not realize what the handful of whites faced.

There they were, a few men, women and children clutching

grimly to a hand-hold along shore, practically safe only under the guns of

their ships. Home and safety was not as now, perhaps 14 hours' flight away, but

weeks and weeks of weary and uncertain voyaging over perilous seas in tiny

ships. The settlers had to depend upon themselves. It is true they had muskets

against the Indian bow and arrow and tomahawk-and scalping

26

knife. It is true that every able-bodied man and boy was a member of the

militia, practically ex officio. It is true that the Indians could not

withstand an attack by a body of militia.

But, the Indian traditionally followed a policy of strike

and run. No one knew when at dawn, they would wake, if they did, to the sound

of the warwhoop with their homes afire over their heads. So, the settlers were

compelled to fight the Indians Indian fashion. They had to match savagery with

even more brutal savagery. The only thing the Indian feared, and thus

respected, was strength greater than he possessed. In other words, the Indian

had to be shown it was not good business to kill a white man, woman or child.

The showing consisted of the settlers killing Indian men, women and children. When

the Great and General Court of Massachusetts put a bounty on Indian scalps just

as it did on wolves and wildcats, it was not mere savagery but sober business.

The Indians killed for scalps; the settlers must be encouraged to do likewise.

The early history of New England is bloody and bitter with

its series of Indian wars -- with the Indians eventually being instigated and

led by first the French and then the British. It is one of the ugliest chapters

in human history -- but it must be read in light of the fact that conditions,

social, religious, economic and moral, have changed greatly since the last

warwhoop died away and the Indians were herded into reservations. In passing,

it may be of interest to know that the Indians of New England, after being

reduced to a mere fragment, are today increasing in numbers again. There are

more Indians in New England now than there were in Civil War days.

The occupation of this area by humans before Boston was

settled is obscure. Apparently, the original inhabitants, so far as is known,

were the so-called Red Paint People. Graves have been found in Maine with the

skeletons dyed red and with pots of red pigment buried close beside.

Evidently, the Red Paint People were pushed out or exterminated

by a nation of small-statured and swarthy aborigines who occupied at least all

of northeastern America. How long they were here, where they came from -- and

all the rest, is a matter of mere legend.

Very likely, the small, dark people were in turn pushed

out, by the familiar Indian of recorded history. These Indians, the red-skins,

may have migrated out of Asia long, long ago, crossing into Alaska via the

Bering Straits. Slowly these Indians made their way down the Pacific Coast,

going southward until they either came into conflict with the tribes of Mexico,

possibly the Mayas and the Incas, or their predecessors. Anyhow, the tide of

red Indians turned left and came eastward across the Rockies

27

and into the great Mississippi Basin, There, they moved north as well as east.

Finally, a portion of them occupied the Northeast, pushing out the small, dark

people mentioned. The exiles seem to have gone north and east and it is

possible that they are today either the Esquimaux or else their blood runs in

Esquimaux veins.

The red Indians in the North East were members of what is

called the Algonquian Nation -- an immense but very loose con-federation of

tribes. Practically, the only reason for such a nation being established by

scholars is that the tribes so united spoke a language with a common or

Algonquian stock.

For greater concern, the Eastern Indians were so-called

forest Indians which is to say their culture, being dependent upon the forest

which covered their holdings, was very different from the culture of the

Indians of the Great Plains, where trees were almost unknown, where the staff

of life was buffalo. It is these Plains Indians, such as the Sioux, proud,

fierce, eagle-nosed, and very accomplished fighters, that set the standard of

the popular idea of the Indian. Eastern or woods Indians did not have horses to

ride, nor did they wear the picturesque war bonnet. They were extinguished with

comparative ease while the Sioux, for example, stood off the Army of the United

States, such of it as was employed, for more than a generation.

The Indians of New England were sharply divided into various

tribes -- although this word is actually a very loose term. The white settlers

from England had a habit of naming the Indians according to the locality in

which they lived, being particularly fond of naming a "tribe" after a

river -- as the Kennebecs and the Penobscots in Maine. The French settlers also

bestowed tribal names and the result was that historians are somewhat confused,

since often the same group of Indians were given two or even more names. Thus

the Indians who lived in Winthrop and vicinity have not been positively

identified as to their tribe. There is a general understanding that they were

members of the Massachusetts tribe but that is indefinite. Perhaps, as some

authorities assert, the Indians of Metropolitan Boston were Pawtuckets. The

point is unimportant. The serious point is that these Indians when the Puritans

came were in a sorry condition. This was a very. fortunate circumstance -- for

the settlers.

The old Norse sagas speak of the fighting quality and the

strength and numbers of the Indians. Armed with swords, the Vikings, who were

the best fighting men of Europe at the time, were no match for the savages -- who

probably overwhelmed the Norsemen by sheer force of numbers and thus

extinguished the colonies, or colony. Certainly, after the experience of the

Vikings, Europeans had a healthy respect for the red men.

28

No one knows how many Indians lived in and around Boston in the early days.

Fishermen had frequented the coast, including Boston Bay, for many years prior

to "discovery" and settlement. These traded with the Indians somewhat

and, on the whole maintained a friendly relationship -- since the fishermen did

not try to settle permanently. From reports of these rough and ready spirits,

strange tales found their way into the British mind. The woods of New England

were imagined to be filled with wild beasts as horrid as anything a modern

geologist can imagine while the Indians were counted as being "numberless

as the leaves upon the trees."

One of the first and, possibly best estimates of Indians

numbers, although it is probably greatly exaggerated, is that made by the Sieur

Des Monts, who anchored his little ships off the Winthrop shore, towards

Noddle's Island, in 1605 and named Boston Harbor, Port St. Louis, and claimed

the area for the King of France.