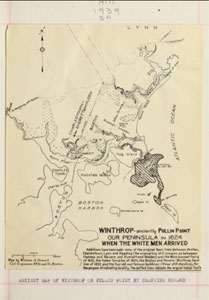

Map by Whitman & Howard, Civil Engineers, 89 Broad St., Boston. Ancient Map of Winthrop or Pullen Point by Channing Howard

CONTENTS

BIBLIOGRAPHY Acts and Resolves of Province of Massachusetts Bay, Vol. I, IV Bailouts Pictorial Magazine, 1857 Major General William Francis Bartlett, 1905 Frederick w. a. s Brown, A Valedictory Poem (1819) Boston Town Records Boston Advertiser. 1856 Boston Post, 1856 Boston Record Commissioners Report, Vol. VIII (1715) XIV (1764) Boston Herald, 1856 Mellen Chamberlain, History of Chelsea, 1908 Chelsea Selectmens Records 1839 - 1778 East Boston Argus-Advocate, 1871 History of the Humane Society (1877) E. Alfred Jones, The Loyalists of Massachusetts James Lloyd Homer, Notes on the Sea-Shore (1848) Journals of the House of Representatives of Massachusetts, Boston Public Library, XXG. 342.12 Letter Book of Francis Bernard, 1760-65 Massachusetts Archives, cxiv, 17, (1739) Massachusetts Historical Society, Collections 5, VI, VII (1882) Massachusetts Soldiers Sailors and Marine (1908) Memoirs of Lucius Floyd, 1855-1865 Methodist Church Records, 1820-1880 Records of Massachusetts Bay, Vol. I (1634) Report of Winthrop School Committee, 1 853 - 1880 Rumney Marsh Church Book, 1729 Nathaniel Bradstreet Shurtleff, A topographical and Historical Description of Boston (1890) Suffolk Deeds , Liber I Suffolk Deeds, Liber 36, 56, 81, 96. William Hyslop Summer, A History of East Boston (1858) Moses Foster Sweetser, King * s Handbook (1885) William Tudor, A discourse before the Humane Society (1817) Enoch Cobb Wines, A trip to Boston (1838) Justin Wins or. Memorial History of Boston , 1880 John Winthrop, History of New England, 1650 - 1649 William Wood, New England’s Prospect (1634) Winthrop Sun and visitor, 1912

INTERVIEWS WITH THE FOLLOWING WINTHROP RESIDENTS Porter Tewksbury Amanda Floyd Channing Howard Wallace Wyman Captain Bert Wyman Mollie Haggerston Lougee William Gray (deceased) George Robie (deceased) William Bam Mrs. John Flanagan Earl Beddoes Ann Morgan Mrs. John White

THE HISTORY OF WINTHROP Edward Rowe Snow INTRODUCTION As the visitor to America looks westward while the ship, on which he sails, passes Graves Light in Outer Boston Harbor, he sees, outlined against the sky, a high promontory where stands the silver-gray silhouette of Winthrop’s most dominating landmark, the water tower. It cannot be determined how many years have elapsed since the first white man viewed this Cottage Hill drumlin, but it is well over three hundred. It is even possible that the Norsemen saw Great Head around 1003 A. D. Other travelers who undoubtedly noticed the Winthrop promontory include Giovanni Verrazano, Bartholomew Gosnold, John Smith, and Myles Standish. 1 The contours of the Winthrop area have changed but little since the first red man visited its shores. It is a queerly shaped peninsula, joining the mainland at Beachmont and having an area of slightly more than 900 acres. Except for this small strip of beachland (fifty yards wide) connecting the town to the rest of the North Shore, Winthrop is surrounded by water. The broad Atlantic beats against

its beaches on the East, the usually placid waters of the harbor caress its western shores, and Belle Isle Inlet separates Winthrop from Orient Heights to the northwest. There are three hills in Winthrop of enough prominence to mention. The area known as the Highlands is really a double hill, rising at its highest point to a level 82 feet above the sea. At the other end of the town. Point Shirley Hill once stood 55 feet high, but twelve feet were removed from its summit in 1907. Cottage Hill, sometimes called Great Head or Green Hill, is the highest promontory in town. It rises to a height2 of 105 feet" above the surf which pounds below it, and is the favorite lookout for residents of the town.

PART I. 1615 - 1755 Winthrop has had many names and titles during its existence. Pullen Point, Rumney Marsh, Winissimett, Chelsea, Point Shirley, and North Chelsea, at one time or other, have all included the area we now call Winthrop. In September, 1634, it was agreed that Winissimett should become part of Boston with provision that the town should "have inlargement att Mount Wolotson and Rumney Marshe".3 The earliest known inhabitants of Winthrop were the Indians, called the Rumney Marsh Indians, in reality a branch of the Pawtucket Indians, part of the great tribe of Aberginians. Two events had served to cut down the activity of the red men to an almost negligible quantity by the time the white men arrived. The first event was the great war with the Taratine Indians, who overwhelmed the Pawtuckets and killed a large percentage of their population in 1615. The second disaster was the great plague of smallpox, which harried the Indians the very next year, 1616. The Indian chieftain of the section including Winthrop was Nanapashemet. Although he survived both the war and the epidemic, his enemies killed him in 1619. After his death the Indians seem to have withdrawn from the peninsula and to have settled around what is now Revere.

A few years later the first white settler of this area arrived. He was Samuel Maverick. Building a residence on what is now Marine Hospital Hill in Chelsea, he fortified it in time to repulse the Indian attack of 1625. The red men never bothered him again. Five years later, June 17, 1650, Samuel Maverick received John Winthrop and the Puritans at his palisaded home in Chelsea. Maverick is believed to have been the son of Reverend John Maverick of Dorchester, and had probably arrived in America with Gorges.4 An explanation as to the reason for the settlement of the Winthrop area would be fitting at this time. In December, 1634, Boston granted lands within its limits to several of its inhabitants, including John Winthrop, Coddington, Bellingham. Cotton, and Oliver, allowing them to divide and dispose of all lands not yet in the lawful possession of any person. We know that the poorer people of the Puritans were given lands near Muddy River in Brookline but the wealthy inhabitants who had servants to till the soil were allowed larger tracts of land at Rumney Marsh and Pullen Point, across the bay from Boston, with either servants or farmers tilling the soil or

grazing the cattle for their landlords. There are just a few of the other early settlers who can be connected in any way with Winthrop. William Noddle, after whom Noddle's Island in Boston Harbor was named, undoubtedly trampled up and down the shores of Winthrop many times before his sudden death in 1632. One day, when he started a trip in his canoe with a great load of wood, the canoe overturned and William Noddle was drowned.5 We know nothing of his genealogical relationships. The next important settler was Job Perkins, who in 1632 was allowed the areas of Pullen Point and Noddle’s Island on which to exercise his exclusive privilege of catching fowl with nets.6 Three years later Perkins moved to Ipswich, becoming deputy at Boston from there in 1636. The General Court appointed William Cheesborough to take care of the cattle in the Pullen Point palisade February 23, 1635. Probably he was the first resident of Winthrop who lingered any length of time. He moved away to Stoughton, Connecticut, three years later.7 Edward Gibbons moved to Winthrop around 1640. A colorful and romantic figure, he caused much trouble in the

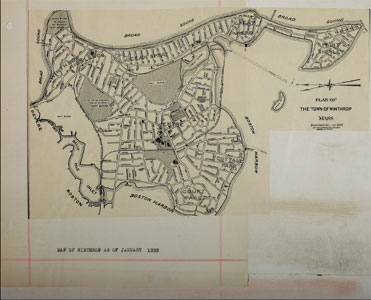

Map of Winthrop as of January 1939

early days of the Puritan Colony. We first hear from him at Mount Wollaston with Thomas Morton and his riotous followers. He then became intoxicated on board the Friendship, running the vessel ashore on Governor’s Island, and was fined twenty shillings for his indiscretion.8 On February 17, 1641 Gibbons and his wife achieved everlasting fame by riding from their Winthrop residence right across the ice to Boston in their sleigh.9 Two and a half years later, Mrs. Gibbons was rowing her children near Governor's Island when she was hailed by the notorious Frenchman LaTour,10 who had sailed into the harbor, anxious for information about Boston. Frightened, she landed her craft on Governor's Island where John Winthrop was then living.11 Winthrop soon arranged matters to the satisfaction of every one, and Mrs. Gibbons reached Pullen Point in safety.12 We shall now take up the Winthrop family in some detail. The General Court, on November 6, 1637, gave John Winthrop the “twoe hills next Pullen Point13 provided it be no hindrance of the towne settling up a ware in Fisher’s Creek, or of fishing for basse there”14

Famous for the great number of trans-Atlantic trips in his day, William Pierce had built a residence in Winthrop around 1657. Coming to New England with Cotton and Hooker, on January 29, 1638, he was alloted 100 acres of land in Pullen Point. Deane Winthrop purchased the house and land from William Pierce on December 6, 1649, and became Winthrop’s largest landholder. His father, John Winthrop, had died some months previously. Thus, at the age of 25, Deane Winthrop became one of the outstanding men of the community. Deane Winthrop had left England for America aboard the Abigail , under Captain Richard Hackwell July 10, 1635. A letter which Deane wrote his brother John has been preserved. Dated March 1, 1648,15 the letter mentions a gun which John sent him from his colony at the mouth of the Connecticut River. Deane goes on to say that the “pinnis that should have broght it did not return backe againe" . Deane purchased another gun, however, and was able to rid the land of the wolves which bothered his cattle. Fourteen years passed, Deane Winthrop married the stepdaughter of President Dunster of Harvard College, and the couple had nine children in all. Perhaps Deane, through the years, had grown dissatisfied with his position in the community. On December 16, 1662, he was anxious to move. He had “some thoughts of remouing from the place thet I now liue in into your coloni16 if I could lit of a convanent place. The

pleace that I now Hue in is litel for me, --mi children now groweing up". One of the earliest known shipwrecks off the Winthrop shore which occurred in 1682 concerns Deane Winthrop. On November 28, 1682,17 Captain Horton’s ship from Nevis entered Boston Harbor during a driving snowstorm and crashed on the Winthrop Beach. A cargo of silver was washed overboard, and three sailors were drowned. Ten men made their way to shore and started for the Deane Winthrop residence. Four froze to death before they could reach the residence, but the remaining six attained their goal, and were received by the Winthrop household. By this time the old Indian trails were no longer adequate for the visitors to Pullen Point, and plans were made for improving travel conditions. After considerable waiting, on April 30, 166618 the General Court chose John Tuttle, William Hasey, and Samuel Davis to plan the highway from Rumney Marsh to Pullen Point, but no documents have been found to indicate just what they accomplished. Incidentally, Tuttle had been accepted into that select group of people known as freemen the year before. Captain Edward Gibbons, the soldier, rose to be major general of the Colonial troops by 1650, but died in 1654. At

the time of his death he owned land at Hog Island, as well as Winthrop. In 1657, this property was purchased by James Bill. Without question, this Pullen Point resident, James Bill, has more living descendants in Winthrop than any other colonist.19 Before 1645 he had purchased land from Wentworth Days. Born in England in 1615, he had probably moved to Winthrop about 1655. By 1650 he was living in Captain Gibbons’ old residence. It is believed that when his sons grew up they moved over to the Bill House, formerly located on Beal Street.20 On the 19th of December, 1686, the frigate Kingfisher sailed past Pullen Point on its way to Boston, bearing Sir Edmund Andros, the new governor of New England. Historians differ as to his proper position in history, but Andros proceeded to impose taxes and imposts which showed the colonists that the days of lenient governors were over. Andros took over the Old South Meeting House for his Episcopalian services, and in many ways turned the population against him. While Andros was absent in Hartford, plans were probably made back in Boston for a united opposition to his rule, and it was arranged that Increase Mather be sent to England in protest. In April 1688, Mather made ready for his trip on the President, but Andros directed that the ship be sent away ahead

of time. Mather, not to be outdone, made private plans to reach the ship, which anchored near Deer Island, and after a circuitous journey by land to Winthrop, Mather rowed out from Pullen Point through Shirley Gut and reached the ship. Many believe today that Andros has been severely handled by the historians of America. The case of John Pittom should be considered in any survey of Andros’ personality. Pittom, a resident of Deer Island, was set adrift in a boat with his family in 1688 because he refused to pay taxes on the land. High Sheriff Sherlock stationed two of his constables on Deer Island to see that Pittom did not return. Incidents such as the Pittom affair were taking place all over Boston. Even the substantial bulk of Samuel Sewall was not free from the Andros shadow, with Sewall receiving notice to pay a tax for his Hog Island property. The Andros revolution intervened, however. When news arrived in Boston that King James II had fallen and that William of Orange was on the throne, plans were quickly completed for a revolution against Andros. On April 18, 1689, New England’s first revolution of consequence began.21 Andros was captured, along with his deputies, and locked up in the Town House, after the declaration of disapproval had been read to him. Andros was later taken.

over to Castle Island, where he was confined in a dungeon for the next ten months. After a few attempts to escape had failed, Andros wrote to England asking to be released, and the next year reached his home across the water. His next position was as Governor of Virginia, where he helped to establish the college of William and Mary.22 Back at Pullen Point, Deane Winthrop watched his family grow up, and spent much time worrying. He had completed his last service to the community by surveying the road from Pullen Point to Winissimet, in the spring of 1699.23 In July of the same year, his daughter Mercy was married to Atherton Haugh. Samuel Sewall was present, and records the incident in his diary.24 Sewall mentions the death of Deane Winthrop, March 16, 1704, "Mr. Deane Winthrop dies upon his Birthday. 81 Years old. He is the last of Gov. Winthrop’s children.”25 The three sons of James Bill received their father’s estate in 1688. James Junior was given the land from Cottage Park along what is now Washington Avenue to Fisher’s Creek. Bill’s other two sons, Jonathan and Joseph, had equal shares of the remainder. When Captain Edward Hutchinson died, James, Jonathan, and Joseph Bill received equal shares of his land

in Winthrop, including Apple Island. The holdings of property by various individuals is skillfully handled by Mr. William Johnson on his plan of October 21, 1690. The last known change in the affairs of the Bill family in this chapter occurred on February 1, 1709, when Elizabeth Reynolds, a widow, conveyed the six acres of land in the Cottage Park section to Joshua, grandson of James, and son of Jonathan. Joshua kept the property for six weeks, soon selling it to his uncle Joseph for a profit of about 4 pounds on his original investment of 23 pounds.25 In the spring of 1714 Joshua Bill’s two sons, Jonathan and Joshua, Junior, were caught hunting and shooting foxes on the Lord’s Day. Jonathan paid the costs in court, and the two men were released. The Bill family probably used caution and deliberation in later years if they felt the necessity for hunting on the Sabbath. The section now known as Winthrop has been inhabited for many score years, during which time hundreds of fishing trips have been made from Pullen Point. The first fishing expedition on record began on the morning of July 17, 1705. The oft-mentioned diarist, Samuel Sewall, headed this early morning trip from what is now Winthrop Beach, and fishing luck was equal to that of some modern fishermen. Anchoring between the

Graves and Nahant, the group caught only three codfish. Sewall’s captain on the trip was old Captain Bonner, father of the John Bonner who drew the famous map of Boston. ^27 Conditions in Europe were now so serious that the residents of New England feared a French invasion from Canada. In answer to frantic appeals, the British ministry promised five regiments of Marlborough’s army to be sent to Boston. The people of Pullen Point looked over from Great Head and saw immense barracks being raised three miles away on Camp Hill, while Pemberton’s island four miles to the south was being prepared for the sick soldiers of England’s finest troops. Month after month went by, but the soldiers never came. Then word arrived that the five regiments had been diverted to Portugal. A year passed, when one day an observer on Pullen Point Head saw many sails far at sea. The people were quite worried before they identified the ships as English men-of-war and realized the long-awaited armada of Sir Hovendon Walker was actually in sight. Ship after ship slid in between Deer Island and Nix’s Mate, ^28 until the harbor was crowded with spars and masts. Marlborough* s regiments had arrived. As the anchors from Sir Hovendon Walker *s flagship slid into the water the people from Rumney Marsh, Winissimett and Pullen Point realized that this fleet of 61 warships was anchoring in Boston Harbor. ^29 ^27. M. H. S. C., Diary of Samuel Sewall, Vol. II, P. 154 ^28. Broad Sound Passage was not then available. ^29. A view of the fleet is at the Bostonian Society.

As Sir Hovendon Walker anchored his mighty fleet of English warships off the shores of Pullen Point, the people of this section knew that thrilling days were ahead. Boat after boat was sent ashore on Noddle »s Island at Camp Hill, and each craft carried over two score of Marlborough* s finest soldiers. Hundreds of tents were soon erected on the hill, and when the sun went down our forefathers saw it set into a vest tent-city of soldiers. The next day the farmers took time off from their tasks to watch the soldiers parade up the easy slopes of the island, marvelling in the precision and grace of the fighting Englishmen. On days when the wind came from the West, the martial music would float across the water, and Pullen Point farmers would enjoy to the fullest the strains of many forgotten airs. ^30 It was a rare spectacle - thousands of the finest troops in the world, the men who had driven the French half across Europe and defeated them at Blenheim, parading in all their glory before the farmers of Pullen Point. England, however, was about to suffer humiliation. The fleet soon left Boston Harbor, and after a few weeks’ news came that the entire expedition had failed dismally and was then limping back to England. Walker was later publicly demo-ted and spent the rest of his life in retirement. ^30. William H. Sumner, History of East Boston, P. 87

At eleven o’clock in the forenoon on Sunday, October 21, 1716, a strange occurrence took place which affected all eastern Massachusetts. The good people of Pullen Point were over at the Rumney Marsh Meeting House, listening attentively as the second hour of Cheever*s sermon began. Gradually the interior of the church grew dim, so dark that those on one side of the aisle could not see their friends on the other side of the church. The long -remembered "Dark Sunday" was upon them. In many churches of New England that day the services were stopped, but we do not know what happened at the little church at Rumney Marsh. Cotton Mather, whose great-grandson preached the first recorded sermon at Pullen Point, sent an account of the "Dark Sunday" across the water to the Royal Philosophical Society in England. The cause of this strange darkness was never determined. ^31 The autumn which included this dark day was followed by an unusually severe winter, with the highway covered by five feet of snow before December 30. Although not an extremely cold winter, it is doubtful if the snowfall has since been equaled. On February 6, 1717, there were drifts 25 feet deep and Cotton Mather said that the people were "overwhelmed" with snow. The "Great Snow" of 1717 began February 18, and lasted ^31. S. Perley, Great Storms of New England, P. 29

until February 22. Again, on February 24 snow fell, and by this time all communication had stopped. The 24th was Sunday, but the people of Pullen Point could not leave their homes. Several one-story buildings were completely covered. Reverend Cheever had to omit the regular services in the Rumney Marsh meeting house, for the ground was covered on the level to a depth of ten feet! In 1720, the Deane Winthrop farm was divided into four sections. John Grover, as Deane’s grandson, owned one-quarter of the 560 acres. He purchased two more quarters, one from his brother, Deane Grover, and another from his cousin, Priscilla Haugh Butler. Joseph Belcher bought the remaining quarter consisting of all the land from Pullen Point Gut to Deane Winthrop »s old house, from Priscilla Adams Royal, grand-daughter of Deane Winthrop. ^32 Our grandfathers remembered the Minot *s Light storm of 1851, when the great waves swept across what is now Winthrop Beach. The tide that year rose to the amazing height of 15.74, but the "Great Storm of 1723” pushed in a tide of 16 feet! The damage to the Pullen Point section must have been relatively heavy in 1723, but no records are available. Some idea of the high tide may be gathered by the contemporary statement that Long Wharf was under three feet of water, while a boat could navigate what is now Devonshire Street in Boston. ^33 ^32. Suffolk Deeds, L 56 ff 15, 16. ^33. Although there are no pictures in existence of the 1723 storm, there is a sketch of the Boston Custom House in the storm of 1851, surrounded by three feet of water.

Sunday evening, October 29, 1727, was a bright moon-light night, and most of the residents of Pullen Point had retired by 10:40 P.M., when a terrible roar and shock awoke the inhabitants and tumbled them out of bed. It was an earthquake. Dwellings swayed and everyone prayed for deliverance. Those who had been awake said that first the noise had resembled distant thunder. Then the rumbling grew louder, until it was similar to the sound made by heavy carriages driven over pavements, but much fiercer and more awesome to listen to. Then the shock became more violent and the houses rocked and trembled. Another quake followed at eleven o’clock, with two more shocks at three and five in the morning. Thus, passed New England’s first great earthquake. Three years later the first representative of one of the three leading families of Winthrop arrived. John Tewksbury became a resident of Pullen Point in the year 1730. He was the son of Henry Tewksbury of Newbury, and the grandson of Henrie Tewksbury, who was made a freeman in Newbury in the year 1669. John Tewksbury was the first of the name to settle in what is now Winthrop. The ecclesiastical and educational development of this area was relatively slow. Because of the sparse population, it was not until the close of the seventeenth century

that definite plans were made for the mental and moral improvement of the residents of Rumney Marsh and Pullen Point. The people gradually became conscious of the need for religion and learning. Those eager to improve themselves could travel to Boston but many from this section wanted instruction and guidance at home. The town fathers of Boston were postponing any action involving financial expenditures, as they hoped to receive the funds from the will of Governor Bellingham. When the people of Pullen Point and Rumney Marsh petitioned for a school in 1701, they were told to await the outcome of the will contest. In the pages of the Record Commissioners Report, for 1701, we read that, "The inhabitants of Rumney Marsh standing by and seeing the town in so good a frame also put in their Request yt a free school might be granted them to teach to Read, Write and Cypher. It being put to the Town to know their minds, it was voted in the affirmative with this proviso. That it did not appear to the selectmen yt there were a suitable number of children, to come to school.” ^34 We read that the selectmen agreed that as soon as Rumney Marsh was large enough for a school the people would get it. Eight years passed, with the children either going with- out their education or receiving it when ever their parents ^34. Boston Record Commissioners Report. Vol. VIII, P. 1.

could spare the time to instruct them. Finally, a red-letter day in the history of the section arrived - February 7, 1709. On that epochal day, the Boston selectmen elected Mr. Thomas Cheever to "attend the keeping such school at his house, four days in a week, weekly, for ye space of one year Ensuing, & render an accot. unto the Selectmen, once every quarter ... He shall be allowed & paid out of the Town Treasury after the rate of Twenty pounds p annum.” In Mr. Cheever’s account we find names of the following families who attended the first three or four years: Tuttle, Floyd, Brintnall, Lewis, Leathe, Wayt, Chamberlane, Hasey, Cole, Pratt, Ritchison, Belcher, and Cheever. ^35 We must keep in mind, of course, that Mr. Cheever’s house was not in what is now Winthrop, but Beachmont, although he spent much of his time in this section. He married the daughter of James Bill, Senior, sometime before 1702. The religious people of Pullen Point and Rumney Marsh had been receiving instruction either at Boston or privately, and in 1706 believed the time had come to have a church of their own. The Town of Boston took action and appointed a committee of five with Samuel Sewall the outstanding member. Month after month went by, with no definite decision. The people became impatient and presented a petition on March 14, ^35. Boston Record Commissioners Report , Vol. XI, P. 85

1709, asking for action in the near future. One of the committee- men, Joseph Bridham, had died, but Edward Bromfield was appointed to take his place. The other members, sewall, Elisha Cook, Elish Hutchinson, and Penn Townsend, met with Bromfield. The committee suggested that 100 pounds be appropriated for a meeting house at Rumney Marsh. Strange as it may seem, twenty people signed a petition against the erection of the meeting house at what is now Revere, and the Bill families of Pullen Point outnumbered the others. Joshua, James, Jonathan, Jonathan Junior, and Joseph Bill all signed the petition against locating the church at what is now Revere, although they must have realized that it would be centrally located for residents of Lynn, Malden, Pullen Point, and Winissimett. ^36 After signing their names, they accepted the inevitable, for the meeting house was begun July 10, 1710. Samuel Sewall sailed down from Boston eight days later to view the meeting house, preferring the breezes of the harbor to the heat of the countryside. ^37 It was a very hot day as several people died of the heat at Salem. Three months later, on October 6, 1710, the sone of Lieutenant Hasey gave the lot to members of the church. ^36. Boston Record Commissioners Report, Vol. VIII, P. 35. ^37. M. H. S. C., Diary of Samuel Sewall, Vol. II, P. 283

As we said before, Thomas Cheever was the first school teacher in this section. Cheever, a graduate of Harvard, 1677, was dismissed from the church in Malden in 1686. He then made his living by tutoring the children of the surrounding area and was often seen at Pullen Point. He became the official instructor for Rumney Marsh and Pullen Point February 7, 1709. Mr. Cheever was ordained the pastor of the Rumney Marsh Meeting House on the 19th of October, 1715. Thus the educational and ecclesiastical reins of Rumney Marsh and Pullen Point were placed in the hands of one man - Thomas Cheever, the Harvard graduate. ^38 Immediately after the conclusion of Reverend Cheever’s sermon October 19, 1715, the members of the church met with Dr. Cotton Mather who had come down to Rumney Marsh to investigate conditions, at the new house of Worship. After the reading of the covenant. Dr. Cotton Mather gave it his official approval, and invited the congregation to join the conference which included the churches of thesurrounding countryside. They were happy to accept the honor. One of the first steps was to obtain a communion service for the church. John Floyd gave ten pounds for a silver cup, with the rest of the service donated by other members of the congregation. ^38. Boston Record Commissioners Report, Vol. VIII, P. 59, 60, 61, 62. ^39. The silver cup is still preserved by the Unitarian Society of Revere.

The Rumney Marsh church was represented in the council of 14 churches which met at Watertown on the 2nd of September, 1729. The meeting was for the purpose of discussing the accusations against Reverend David Parsons, the pastor of Leicester Church. It was finally decided that Reverend Parsons had been shamefully treated by his congregations, so after passages from John 13 and peter 1 had been read the brethren were admonished to "put away from you all bitterness and wrath.” ^40 March 1, 1734, it was announced that Deacon John Chamberlain was going to move over to Pullen Point. He gave up his duties as treasurer of the church to the new treasurer, turning over the sum of twelve pounds and eleven shillings. In a few months Deacon Chamberlain was firmly established in Major Edward Gibbons’ old residence. He had purchased the Bill farm back in 1726. The residents of Pullen Point and Rumney Marsh agitated for a separation from Boston in 1734. A committee decided against the plan, however, but it came up again the following year. Three years later 24 people petitioned for a break. Included among the petitioners were John Chamberlain, John Grover, and Joseph Belcher, all landowners from Pullen Point. The General Court finally granted the request of the petitioners, and the act of separation was signed by Governor ^40. Rumney March Church Book, P. 217.

Jonathan Belcher, January 9, 1739. ^41 Thus, after an allegiance of 103 years, Winthrop, Revere, and Chelsea broke away from the town of the Puritans, and became part of the North Shore area. ^41. Massachusetts Archives, Vol. CXIV, 499, 500

PART II, 1759 - 1852 Now that the two areas, Pullen Point and Rumney Marsh, had been set apart from the rest of Boston, and given the name Chelsea, the residents began to wonder if they had done the wisest thing possible under the circumstances. But the die was cast. Speaker Quincy of the House of Representatives ordered Samuel Watts of Chelsea to assemble the voters at a town meeting scheduled for the first Mondayof March, 1739, for the purpose of choosing their town officials. ^42 Constable Samuel Floyd notified the residents of the town meeting, and at 10:00 a. m., Monday, March 5, the voters met in the vestry of the new meeting house. Samuel Watts was made moderator and Nathaniel Oliver town clerk. During the afternoon, the entire official list of officers for the town of Chelsea was drawn up before the meeting adjourned. A second meeting was called for March 20. This meeting was made necessary by the several resignations from the elected board of town officers. It is said that many of the men elected to town office were merely elected because of the fine they would have to pay when they refused to serve in their official capacity. For example, Mr. Elisha Tuttle had been made Surveyor of Highways. The town would not excuse ^42. Massachusetts Archives, Vol. 114, P. 316.

him, so he paid his fine. Jacob Hasey was elected in his place. By 1742 the people were not satisfied with the way the affairs of the town were going. They didn’t know just what was wrong, but wanted to take action of some sort which might improve conditions. They decided that if they were allowed to annex Hog Island and Noddle’s Island, the added land might enable Chelsea to be more prosperous. The inhabitants presented a petition to the General Court asking for the two islands, but the General Court refused their request. Samuel Floyd, the Pullen Point resident, was slowly working his way up the political ladder. Constable in 1739, Floyd became selectman the next year. In 1764 he represented Chelsea at the General Court. After a long career in both church and state affairs, he died at the age of 85 in 1780. ^43 On November 15, 1739, Ensign Joseph Belcher died. He had married Hannah Bill in 1698 and purchased the Deane Winthrop farm in 1720. This area included all of Point Shirley and the beach up to the Highlands. At his death, his widow was left a great apple orchard which stretched all the way up to Cottage Hill. The deed of acquisition in the Pemberton Square Court House mentions several locations of interest. The Beach Bars are generally believed to have been part of a rail fence which ^43. Mellen Chamberlain, History of Chelsea, Vol. II, P. 739

cut across Pullen Point Neck. They had to be taken down when a traveler desired to reach Point Shirley, and replaced after his horse or team had passed through. If the bars were not replaced the cattle might wander all over Pullen Point. ^44 Three other locations are found in various parts of the deed. Attaway’s Gate was evidently similar to the Beach Bars. We believe that it was placed in the general vicinity of the Deane Winthrop House. Ballast Hill was probably Cottage Hill, as ships from early times always came up on the beach near this hill to obtain rocks for ballast. A location known as "The Island" evidently shows us that Point Shirley was practically an island in earliest times. On January 12, 1748, Elizabeth Belcher sold the land formerly owned by her husband, Joseph Belcher, to Thomas Pratt. The sale included all the "Woods, Water, Members and appurces whatsoever thereto belonging". Pratt, however, was only to keep the land a short time. ^46 In the summer of 1748, Ezekiel Goldthwait ^47 made a visit to Pullen Point. He returned in 1749, interested in ^44. Suffolk Deeds, Liber 36, P. 216. ^45. Suffolk Deeds, Liber 81, P. 154. ^46. Suffolk Deeds, Liber 81, P. 155. ^47. Goldthwait was Town Clerk and Register of Deeds.

starting a fishing village, and purchased for 500 pounds practically all of what is now Point Shirley. Four years later, he had interested his brother Thomas Goldthwait and six other men. In 1752, Ezekiel Goldthwait accepted the seven men into partnership in the fishing venture. Saving a quarter interest for himself, he sold his brother an eighth share. The other men, John Rowe, who built Rowe’s Wharf in Boston, Henry Atkins, formerly a Boston selectman, together with Nathaniel Holmes, John Baker, and Thomas Mitchell, all purchased one- eighth shares. Holmes was a prominent Roxbury resident. Baker was another Boston selectman, and Thomas Mitchell later became prominent as a Loyalist. The selectmen of Chelsea were so impressed at the efforts this group of prominent Bostonians were making at Pullen Point that they voted to exempt from taxation the new fishing industry. In the summer of 1753, stately mansions were erected on the hill above the fishing settlement, and Thomas Goldthwait was among the first to make his home there. Thomas Goldthwait, throughout his residence at the Point, occupied a leading position in Chelsea affairs. At one time, he represented Chelsea in General Court; at another, he was one of three commissioners chosen to settle the affairs of the Land Bank. ^48 The owners of the fishing village planned a great celebration for September, 1753. At this time, as Governor ^48. Acts & Resolves of Province of Mass. Bay. t Vol. IV, P. 189.

Shirley was in Boston, the proprietors went to him, asking if he could be present for their exercises. He agreed. Four years before, he had laid the cornerstone for the new King’s Chapel, and many members of that church were financially interested in the new project at Pullen Point. September 8, 1753, was the date chosen for the great event. The wharf of John Rowe was probably the starting point for the party on that festive day in September. As the ship sailed down the harbor, there were no fireboats to cheer the voyagers with their parabolas of water, but there was something else equally effective. A new battery of guns, named for Governor Shirley, had recently been constructed on the shore at Castle Island. When the vessel drew abeam of the old fortress, a salute of fifteen guns was given the old soldier by the men at the Castle. As the cannon shots echoed and re-echoed across the harbor, the populace at the Point went wild with excitement. Soon the craft was visible, and the impatient throng crowded down onto what was then known as Long Wharf. ^49 Gathered around the governor were many gentlemen chosen for their wit and humor, who had joined the party to keep it in merriment. The proud ship slid up to the dock, and the demonstration continued until the banquet started. Then came ^49. The remains of this wharf can still be seen about one hundred and fifty yards to the north of what is known as the old steamboat landing.

the time for the greatest announcement of all, that which has caused the name of Shirley to come down to us while the names of the proprietors are known only to the student of history. Governor Shirley had already agreed to the announcement, which was that Pullen Point was to be changed to Point Shirley, in his honor. The enthusiasm of the crowd was again demonstrated, after which the popular leader gave a speech acknowledging the honor paid him. Then, as the sun was getting low in the west. Governor Shirley and his court boarded their craft and started for Boston. Point Shirley had enjoyed what was perhaps its greatest day. In the Boston Public Library, there is an original document of around 1755 containing a list of men eligible to fight, who were then living at Pullen Point. The sixty-six men making up the list probably had families of from four to six each, so we can roughly estimate that the population of Winthrop at this time was at least 300. The members of three old Winthrop families are mentioned - Nathaniel Belcher, John Belcher, Andrew Tewksbury, who was the father of lifesaver William Tewksbury, Jonathan Bill and Charles Bill. ^50 Thomas Goldthwait had been heavily in debt when he moved to Point Shirley, and Ezekiel decided to let him run the business there to make up the several hundred pounds Thomas was then owing. ^51 The town of Boston helped the enterprise by ^50. Boston Public Library, XX G. 342. 12. ^51. Josiah Ouincy and James Boutineau had each lent him 300 pounds.

leasing Deer Island to the proprietors for the nominal sum of 20 shillings a year, provided the industry use twenty ships from Boston. ^52 In 1758 the members of the town meeting asked the proprietors if they had complied with the terms of the agreement. The proprietors replied that because of the intervention of the French Wars they had not carried out their agreement. Since three or four vessels had been captured by the French, they could not become active again until the war was finished. From the termination of the fishing business until the end of the war. Point Shirley was used for other purposes. In 1759 troops waiting to be sent to war were quartered at the buildings in Point Shirley. Because of the British distrust of the inhabitants of Beau-Sejour in Acadia, 12,000 Acadians were taken from their homes and distributed along the coast. More than a thousand of the exiles were eventually landed around Boston Harbor, and the fishing village of Point Shirley received its share. In the letter of Governor Bernard to Jeffrey Amherst, dated September 5, 1762, the Governor states that he "allowed some sick women and children on shore at Shirley Point; where the whole might be accommodated; if the expence was settled and there might be a guard . . . set over them, if they had clothing (as) they brought two months provisions with them.” As late as 1765 ^52. Boston Record Commissioners Reports. Vol. XIV, P. 236.

there were 1100 Acadians in Massachusetts. ^53 Colonel Thomas Goldthwait had assumed control of the fishing industry early in 1754, but the subsequent developments in the French War had placed him directly under Governor Bernard. When the troops were called out from the counties north of Boston, arrangements were made by Goldthwait to have them leave Boston Harbor from his fishing wharf. Goldthwait quartered the troops at Point Shirley until late in the Spring, when they sailed from Long Wharf, Point Shirley, to Louisburg. Much had happened at Point Shirley, however, in the years between 1753 and 1759. Recalling the prosperous village of 1753, with over sixty men of voting age in the community, we can see to what depths the settlement had fallen by visiting the little fishing village three years later, in 1756. Four men whose names were on the original list still remained. We cannot tell if the families of the men in 1753 accompanied them. We do know that five families then lived at the Point. Nathan Sergeant, a blacksmith, lived in one end of the large fish warehouse on King street, while the other side was occupied by Israel Trask, a maker of sails for harbor boats. Under the eastern part of the hill stood another warehouse, where John Poarch, a lonely fisherman, lived. At the other end of 53. Longfellow’s Evangeline probably received help at Point Shirley. Possibly an old inhabitant still living when Longfellow visited Point Shirley, recalled for the great poet’s benefit, the tragedy of this young Acadian girl who lived there. Stranger things have happened.

the same building lived Elizabeth Poarch, but we shall probably never know if she was his wife or merely a relative. On the Number Two lot of land running from Fish street down to the sea-side there were eight great fish flakes or wooden frames, ready for countless cod to be dried in the sun. Nearby was the store run at the time by Mrs. Clapham, where the men charged their goods. A huge warehouse stood in back of the store. Another lot running from Fish street to the harbor side had six flakes, with another store standing near the beach. A small dwelling in a ruined condition was occupied by Bosworth, the fisherman. Long Wharf pushed itself into the sea for at least 350 feet, according to fairly accurate estimates. Thus, we see that in three years the Point had become almost a deserted village. Three years later, when the soldiers were waiting for the troop ships, the buildings were falling apart. As a means of financially improving their business in 1764, the dreaded sickness, smallpox, was a blessing in disguise to the discouraged proprietors of the Point. It was fatal in effect, however, when it first visited the area. On May 19, 1755, a committee of three was chosen to investigate the money given the people by the General Court because of the smallpox "brought among us by Captain Cussen". The reference is to the ship of horror which was wrecked on Winthrop Beach three years before. The cowardly captain deserted the ship, leaving John Scalley, one of the

crew, ill with smallpox. When the tide went down. Captain Cussen sent his crew aboard the ship, the Bumper, to get Scalley. They returned with the victim, who had died, wrapped in a hammock, and buried him under some rocks. Two days later the corpse was discovered by the inhabitants of Point Shirley. Not knowing the man’s sickness, the people had boarded the ship and taken ashore all usable material. As a result, Bartholomew Flagg, Benjamin Pratt, Samuel Tuttle, and Thomas, Patten died of smallpox. ^54 With the memory of this tragedy still fresh in their minds, the inhabitants of Pullen Point viewed with alarm plans to turn the old fishing center into a smallpox home. The people of Chelsea were very much against the project, but in 1764, the smallpox raged so violently that it was at last agreed upon. On February 14, 1764, the proprietors of the company voted to allow the victims to be landed at the Point. One week later the selectmen of Boston assigned the houses at Point Shirley as a “Hospital for Inoculation.” ^55 April 11, 1764, the lease was finally drawn up between the proprietors and the selectmen of Boston. Two years later, the proprietors were able to rid themselves of the Deer Island problem. April 16, 1766, the ^54. Chelsea Selectmen’s Records, Vol. I, P. 27. ^55. Boston Record Commissioners Reports, Vol XVI, P. 103.

selectmen of Boston leased part of the Deer Island fishery property to Ebenezer Pratt and Samuel Pratt. At that time there was only one house on the island, that in which Captain Tewksbury lived many years later. The people of the Winthrop peninsula gradually came to realize the strategic position of their location. Pullen Point was one of two sheltering arms guarding the Port of Boston, and Shirley Gut was a narrow but effective waterway which could be used in an emergency. As relations with the mother country became more and more strained, the citizens of Pullen Point began to think of defending this part of the North Shore. Tentative plans were made for a fort at Point Shirley. When Benjamin Franklin learned that the dreaded Stamp Act had passed, he wrote his friend Thompson, afterwards secretary to the Continental Congress, that “the sun of liberty has set.” From what is now Winthrop, the farmers and fishermen looked over the harbor noticing many of the ships at half-mast in protest of the act. August 14, 1765, the mob in Boston hung in effigy the stamp distributor, Andrew Oliver, from the old elm known as the Liberty Tree. ^56 When the news reached Governor Hutchinson, he ordered the mob to remove the effigy, but nothing was accomplished until evening. As it grew dark a great throng assembled at the Liberty Tree, and the effigy together with one of John, ^56. Located near what is the corner of Boylston and Washington Street .

Earl of Bute, was marched along Washington street, passing down what is now Newspaper Row until the Old State House was reached. As many as possible crowded into the room directly under the council chamber where Governor Francis Bernard and his assistants were in conference. The crowd then started for Fort Hill, stopping on Kilby street to rip up a great frame where the stamps were to be distributed. When the mob reached Fort Hill, they built a great bonfire and placed the effigies and the frame on the flames. Whether or not the citizens of Winthrop participated in this demonstration is not known, but probably they remained at home, watching the huge bonfire with misgivings and alarm. Almost a century before, the hated Andros had beentaken prisoner at Castle Island. Perhaps Bernard and Hutchinson believed that history would repeat itself, or it may have been they thought that they would be able to be safer at Fort William, where Bernard had his summer home. Before dawn both men had reached the historic island fortress. August 26, 1765, another mob visited the mansion of Lt. Governor Hutchinson, destroying and stealing everything of value in his residence, including thousands of priceless documents. This deed by New England men was a calamity for historians. Samuel Adams, one of the two Massachusetts men who are honored in Statuary Hill, Washington, now attracted attention by his series of fourteen resolves presented to the

Massachusetts Assembly. The resolves were passed by a full house. October 7, the first American Congress met in New York, passing resolves which were sent to the King in England. The chill winds of November arrived with the Stamp Act still in effect, so new rioting broke out when the Bostonians realized the King would not yield. December came and went but no definite action was taken. Back in England, Parliament was reassembled in January, 1765. The venerable Pitt, suffering from gout, was assisted into the hall. After others had spoken, he rose and gave his memorable address. This page is not the place to quote from his speech, but the reader’s indulgence must be asked for the following prophetic utterance: "In a good cause . . . the force of this country can crush America to atoms. Upon the whole, I will beg leave to tell the House what is really my opinion. It is that the Stamp Act be repealed absolutely, totally, and immediately." Pitt’s advice was followed the next month. May 19, 1766, the people of Winthrop joined in celebrating the repeal of the Stamp Act. Two years later two regiments of British soldiers sailed past Point Shirley. They were on their way to be quartered in Boston at the expense of the Massachusetts people. Naturally, the people of future Winthrop were quite indignant when they found out the plans of those in power in England, but

nothing of importance occurred until the second of March, 1770. On that day, a citizen became involved with one of the soldiers, and plans for retaliation by the civilians were made. Three nights later the soldiers were attacked by a mob, which pelted the officers and men with sticks, snowballs, and stones. A moment later a soldier fired, and his companions followed. This event, the Boston Massacre, caused consternation around Boston Harbor. The people were so enraged that the soldiers were sent back to Castle Island for their own protection. The Townsend Acts had been passed in 1767. Their object was to pay for the soldiers and officers of the government, in the colonies. Violent opposition again forced leaders of the English government to modify their plans, so all taxes were lifted except a small tax on tea. The people of Winthrop saw that the English were determined to make the Massachusetts villages and towns pay the tax, so when three tea ships slipped into the harbor in December, 1773, most of the inhabitants decided to abstain from tea in the future. Bostonians, however, took more definite action on the night of December 16, when a group of prominent men, disguised as Mohawk Indians, threw a tenth of a million dollars’ worth of tea into the harbor. The next morning many of the packages floated ashore at Winthrop. After the battles at Lexington and Concord had started the Revolutionary War, conditions around Pullen Point and Point Shirley became acute. The British had stocked the harbor

islands with sheep and cattle, and the Americans realized that the cattle should be taken off to embarrass the English forces. May 14, 1775, the order was issued by the American commander to remove all the livestock from Pullen Point, Point Shirley, Snake Island, Hog Island, and Noddle’s Island. At 11:00 a.m., May 27, Colonel John Stark, the Commander of the American troops in Chelsea, crossed the ford from the mainland to Hog Island. There they were seen by a number of British marines stationed on Henry Howell Williams’ farm at Noddles Island. A short skirmish followed but no American was either killed or injured. The shooting was heard by the men on the British warships in the harbor, and an armed schooner was sent up Chelsea Creek to cut off Colonel Stark and his men from the mainland. The schooner carried four six-pounders and twelve swivels, and was accompanied by an armed sloop crowded with British marines. Colonel Stark directed his men to hide in the marshes of Hog Island. Long, narrow drainage ditches had been dug through the marshes, as is the case today. Soon the ditches were filled with hundreds of Americans, waiting in ambush for the British vessels. When the tide filled up Chelsea Creek the British sailed in, but received a terrific fire from the thousand American soldiers in ambush. The wind now died down, so that the British got out their long boats and began towing their two vessels out of the trap. The

Americans poured volley after volley down on the unfortunate Englishmen, and the Battalions could not find many targets at which to shoot. Two cannons, the first ever used by American soldiers, had been placed by the Americans at the site of the Magee’s Funace Foundry. These two pieces poured their deadly charges down upon the helpless ships. When night arrived, the tide was going out rapidly, and the larger vessel, the Diana , soon was aground. The crew fled as best they could in their long-boats, leaving the luckless Diana to the mercy of the Americans. When the Continental forces went over the side of the Diana , it marked the first capture in history of a British warship by Americans. Although the American losses were light because of their superior plans, those of the English were high. Sixty-four bodies of British marines were landed on Long Wharf, Boston the next morning. ^57 The British, after General Washington established himself at Dorchester Heights, evacuated Boston. They remained on board ship for many weeks in Boston Harbor, continuing the blockade. In December 1775, General Howe, in charge of Boston, ^57 It is said that this battle is relatively obscure because of Frothingham’s desire to give more prominence to the Bunker Hill engagement.

sent hundreds of poor people from that city ashore at Point Shirley to shift for themselves. These poor sufferers passed a terrible winter at the Point, living as best they could in the abandoned meeting house and the other buildings. We now come to the Battle of Shirley Gut. On the 17th of May, 1776, Captain James Mugford was cruising in the outer harbor and detected a British powder ship bearing down on him. Since he knew the various channels around the Brewster Islands, Mugford waited for the powder ship. Boarding the vessel, he acquired control in a relatively short time, and in full view of the British fleet in Nantasket Road, slipped through Hypocrite Channel and made his way toward Shirley Gut. The British were aroused, however, and plans were made to overtake the captured powder ship. The English did not dare to follow the clever captain, however. In maneuvering the ship through the treacherous waters of the Gut, Mufgord ran the powder ship aground. Sending word to Boston for aid, he was enjoyably surprised to see boats of all sorts sailing down to the Gut, and soon the cargo was being unloaded. The powder ship was brought up to Boston at high tide. Two days later. May 19, Captain Mugford on the Franklin , with Captain Cunningham on the Lady Washington sailed down the harbor, but because the tide was too far out, the Franklin grounded in Shirley Gut. This was the chance for which the British had been waiting and Mugford knew it. Going ashore on

Deer Island with Cunningham, Mugford went to the top of Signal Hill and trained his telescope on the British warships. He could see activity on the ships as the men prepared their whaleboats for the trip to Shirley Gut. The two American captains returned to their boats and prepared for the battle. After several warnings, the American ships began to fire at the thirteen boatloads of British sailors and marines. Soon the enemies were at close quarters, and the tide of battle swayed first one way and then another. Tradition tells us that not one Englishman set foot on either boat. At the height of the battle Mugford was shot, and his immortal "Don't give up the ship* admonition was given as they carried him below. A few minutes later the battle was over and the British had fled. Seventy men were lost by the British, while Mugford was the only American to die in this outstanding victory. One of the British whaleboats drifted ashore the next morning near the present location of Sunnyside Avenue, and two children were the first to discover it. When the tide went out they climbed aboard, but were frightened terribly when they saw in it the body of a British Marine killed in the battle. The tradition is that he was buried near the place the children found him. The Revolutionary War left Winthrop in a sad state, but with the surrender of Cornwallis at Yorktown the farmers believed better times were ahead. More crops were planted year by year, until the fields were filled with vegetables, and when

autumn came the barns were bulging with produce. But the winter of ‘86 was coming. The winter of 1786 was one long to be remembered by the people of Winthrop and the surrounding settlements. Boston Harbor had started to freeze over before the end of November, and December began cold and ominous. When the Winthrop farmers arose on the morning of Monday, December 4, they noticed conditions were ideal for a snow storm, and sure enough, before they sat down to their noonday meal, a piercing northeast wind set in. Just about twelve o’clock the first flakes began to fall, and soon a blinding snow storm was raging. The gale became violent, with the visibility lowered to less than fifty yards in any direction. The Winthrop farmers probably stayed inside that afternoon. They were, of course, all good sailors in those days, and probably offered prayers for the safety of the men at sea. Those who have been at sea in a snow storm know the feeling of hopelessness experienced during a bad blow when it is impossible to see more than a few score yards. Three miles from Winthrop, on Lovell’s Island, a packet from Maine went ashore, with the thirteen passengers and crew getting ashore on the lonely island in safety, only to meet what was possibly a worse fate than drowning. After hunting vainly on the island for shelter, they all climbed to the top of a great rock on a hill (which can still be identified) . Here they crouched in the lee while the storm increased

in intensity and the air grew colder. The temperature in surrounding towns that night went far below zero, and before dawn all had frozen to death, except one man, Theodore Kingsley, of Wrentham. Two lovers, who had been among the passengers to Boston, perished in each other’s arms. The roving poet of Boston Harbor, Frederick William Augustus Steuben Brown, who was influential in starting the first Methodist church in Winthrop, tells us of the tragedy: Among the rest, a youthful pair. Who from their early youth; Had felt of love an equal share, Adorned with equal truth Lay prostrate mid the dire alarms. Had calm resigned their breath; Fast locked within each other’s arms. Together sunk in death. The rock where the tragedy took place, now called Lovers’ Rock, can still be pointed out by the island inhabitants The east wind, however, was not yet finished with his fatal work. The brig Lucretia, under Captain Powell, had left St. Croix, the week before with one of the owners, a Mr. Sharp, aboard. The waves which had pushed the little Maine packet ashore at Lovell’s Island, December 4, had not affected the Lucretia, which rode out the night at the edge of the harbor. Tuesday morning, probably at dawn, she slipped anchor and sailed for the pier in Boston. The wind grew stronger, with the snow pelting harder, and the brig crashed on Point Shirley Beach about nine a. m. There were eleven on board and Mr. Sharp, together with the first mate and three of the crew, jumped into

the surf. They succeeded in reaching the deep snow on Gut Plain in safety. The others on board envied the daring of the five ashore, but they, as it turned out, were the lucky ones. The five-ashore floundered around in the snow looking for shelter, until one by one they fell exhausted in the deep rifts and perished. Captain Powell and the rest of the men remained on the Lucretia until the storm ended, and then went ashore. The remains of the five men were gradually dug out of the snow drifts, and Mr. Sharp »s body was taken in state to Boston. His funeral was held in Boston at the American Coffee House, on State street, December 12, 1786. ^58 The farmers hardly had time to recover from the storm when it began again, December 7. By Sunday the highways were hopelessly covered. No religious services were held anywhere around Boston that day as no one could reach the meeting houses. Those who experienced this terrible gale regarded it as the worst of the century. Thomas Hancock, uncle of John Hancock, had become a Point Shirley proprietor. When he died, John took over the property. John Hancock spent many happy summers at the Point. There is still in existence a letter written by Dorothy Hancock, addressed to Point Shirley by way of Apple Island. Evidently the Bostonians considered the waterway between Bird Island ^58. Sidney Per ley. Historic Storms of New England. P. 125.

Passage and Apple Island more efficient than the passage around by the mainland. James Tewksbury, who resided at Point Shirley for many years, had been one of the "Point Shirley Minute Men.” His son, William, became known all along the Atlantic coast for his ability in saving shipwrecked sailors from death. His first rescue took place in 1799. In December of this year, William Tewksbury saved an English sailor who had fallen from a vessel anchored in the harbor. The following year he rescued a sailor from the masthead of a schooner which had crashed off Fawn Bar. At this time, he was assisted by his colored boy. Black Sam, who later perished crossing Shirley Gut. In March, 1809, Tewksbury gained more recognition by saving Thomas Gould from his wrecked pikey boat. This rescue was made at Winthrop Bar, mistakenly called Fawn Bar by many. ^59 On Monday, June 16, 1806, occurred the only total eclipse during the nineteenth century, visible in what is now Winthrop. There had been a light frost the evening before, and the temperature was 63 when the eclipse began. When the eclipse was total, the temperature was down to 55.5, and dew formed on the grass. The journals of the time tell us that the sudden change in the temperature caused the death of some of those who had been overheated, but this statement appears rather difficult ^59. William Tudor, A Discorse before the Humane Society, P.21

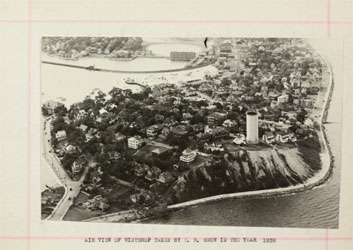

A View of Winthrop taken by E.R. Snow in the year 1939

to believe As the eclipse began, the stars came out one by one until finally Venus was seen in the west, Sirius on the south-east, and Aldeberan, Mars, Mercury and Procyon were plainly discernible. The effect of the darkness on the cattle in the pastures was interesting. Cattle ceased feeding, and started for the barns. Fowls went to roost, and bees came back to their hives. The eclipse was total for more than five minutes, and when the sun again began to peep out and enlighten the world, the joyous crowing of roosters could be heard from all the farms of Winthrop. Fifty minutes past twelve the sun was again free to shine in the heavens, and the Winthrop farmers and fishermen returned to their tasks, perhaps a bit more respectful toward the wonders of the universe, thinking along with Ramsey: "How vast is little man’s capricious soul That know r s how orbs through wilds of ether roll". ^60 We now come to the period in Point Shirley’s history when the hum of business begins anew. Because of the many opportunities in Boston, many young men left Cape Cod and the surrounding area to move to the city. Russell Sturgis, who was born August 17, 1750, was among the first to appreciate the advantages of moving to Boston. He was the son of Thomas Sturgis of Barnstable. Russell ^60. Sidney Perley. Historic Storms of New England.

knew oy heart the process whereby the salt could be extracted profitably from the ocean and believed the ruined buildings and warehouses of Point Shirley could be utilized to good advantage for the salt works. Journeying down to Winthrop early in the year 1803, Sturgis was fully decided that the making of salt would be a good venture, so on March 22 , 1803, he purchased one and one-half rights in Point Shirley for $1200. The following year, the three most important land owners of the Point and what is now Winthrop Beach ^61 agreed to divide their property, hiring Osgood Carleton, a prominent surveyor, to arrange the partition. Carleton worked on the division during the summer of 1804. On September 24, 1804, the three met again and Osgood Carleton’s map was approved. Elisha Baker was of the same family as John Baker, one of the original Point Shirley proprietors. We cannot say definitely when the salt business began at Point Shirley but some day it is hoped we may find some documentary evidence which will help us. Sturgis and Parker were now in charge at the Point, but their partnership was soon to end. On February 11, 1806, Nathaniel Parker sold 79 acres of the land there to Russell Sturgis, for $5000. Russell Sturgis’ younger brother, Samuel, who was born in 1762, had married Lueretia Jennings in 1786. They lived in ^61. Elisha Baker, Russell Sturgis, and Nathaniel Parker.

Boston until December 12, 1811, when Lucretia Jennings Sturgis died of a broken heart because her children had either died or moved away. The month before, their oldest daughter, Lucretia, had married the noted Joshua Bates (after whom Bates Hall is named in the Boston Public Library) and a few years before that their first born, Thomas, had been lost at sea. Samuel was now given the position of running the salt works of Point Shirley and moved into a house on Siren street. ^62 June 19, 1812 the United States declared war against England, but this act was decidedly unpopular in Boston and New England. So confident were the British that the New Englanders would eventually rebel from the rest of the country that they did not blockade Boston Harbor for many months. Finally, giving up hope that this section of the country would favor them, the English decided to prevent commerce to and from Boston. Early in April 1813, the Shannon and the Tenedos appeared off Boston Light. Commander Lawrence now arrived in Boston to take command of the Chesapeake, then undergoing repairs. May 30, he cast loose from Long Wharf, Boston, and dropped down to President Road, where he had the intention of “lying there a few days and shaking down before going to sea". The people in Winthrop saw the warship perhaps a half mile from Point Shirley, and then looking in the other direction could make out the Shannon and the Tenedos, hull down on the ^62. The building is now occupied by the Reed family.

horizon. The next afternoon they could only see one British warship, and so word was relayed to Boston, where Lawrence was having dinner with a friend. Lawrence made immediate preparations to sail into battle, and the next morning the Chesapeake weighed anchor and started for combat with the Shannon. When the people of Winthrop saw the American ship start for the outer harbor, they gathered at Grover’s Cliff and waited for the coming sea fight. As the Chesapeake bore down on the Shannon, the Shannon headed for the open sea and then turned, so that the two vessels came together about five miles off Boston Light. The first cannon shot was heard in Winthrop at 5:50 p.m., and the firing lasted but fifteen minutes, when it was seen that the English vessel had captured the Chesapeake. Among the disappointed Winthrop spectators was Miss Sarah Tewksbury, who later became Mrs. Proctor. In later years she told of seeing the smoke from the cannons and of hearing the reports of the battle. The farmers of Winthrop cheered when the Constitution sailed into Boston Harbor April 22, 1814, but when a blockade of several British ships was begun they became concerned as to whether the famous frigate were not bottled up. The summer went by, and the cool breezes of autumn changed to the penetrating chill of November, but the blockade continued. One calm day in the first week of December several

long boats filled with American sailors came over to Winthrop and landed at Shirley Gut. These men remained there several days, surveying and sounding. They found that at high tide the Constitution, which drew 24 feet, could negotiate the Gut under favorable conditions. Between two of the islands in the outer Harbor is a passage still known as Hypocrite Channel. It is located between Green Island and Little Calf Island. The sailors told Mr. Sturgis that their next goal was this passage, where they were to make accurate surveys and soundings. The following week, the long boats headed for the Outer Harbor, and not only discovered that the Constitution would easily be able to negotiate the passage which James Mugford had used 38 years before, but found one place where the water was 84 feet deep. Preparations were now complete for the escape of the Constitution, and so when an easterly storm swept the coast with unusually high tides. Commander Stewart had everything ready for a quick exodus. When, on December 17, the wind changed to the west, Stewart knew the time had come. Probably an hour before high tide, he weighed anchor off Long Wharf and started for Shirley Gut. What a pretty picture the farmers and salt workers of V/inthrop must have been privileged to enjoy as "Old Ironsides" cut in towards Pullen Point. Reaching the whirling eddies of Shirley Gut at high water, the Constitution swept gracefully between Winthrop and Deer Island.

We can well imagine what a cheer went up from the farmers and the workmen from the Sturgis plant who gathered on the shore to watch the great sight. A half hour later the Constitution rounded Great Fawn Bar, slipped in between the Devil’s Back Ledge and Half Tide Rocks and was sailing between Little Calf Island and Green Island. The Constitution in another hour had left the Brewster Islands far astern and was free. ^63 The salt industry at the Point was supplied by a general store, located near the present Roman Catholic Church. One day the workers at the Point were surprised to see a colored boy of fifteen walk into the store. He obtained a substantial supply of groceries and, when given his bill, paid the amount in English gold. After the colored boy, who told the store people his name was Black Jack, rowed away from the beach, the people watched him land a half hour later at Apple Island. When a week had passed the boy again landed for supplies and before the season had ended, the entire story of this Apple Island colored boy was known. Black Jack had been a young boy in Africa, until he was captured by a slaver, alleged to be Captain William Marsh. Marsh took a fancy to the young colored boy and made ^63. Fawn Bar is spelled with a W, and not with a U, as was indicated by the town when it named Faun Bar Avenue.

him his servant. When the former British naval officer finally-acquired enough fortune so that he could retire, he took Black Jack up to Boston with him. Marsh then married a young lady from Connecticut. They moved over to Apple Island in the year 1814, as Marsh had been attracted by the snug colonial mansion he saw at the top of the hill. ^64 Black Jack visited Point Shirley every month, purchasing such supplies as he needed. The Marsh family grew yearly, until there were twelve children in all. William Marsh, however, passed away on November 22, 1833 and his house was destroyed two years later, forcing the family to move to the mainland. Marsh had been buried at Apple Island, the place he had grown to love. The daughters married into the Winthrop families, and their descendants are still with us. The sons moved away, achieving success wherever they located. This mysterious captain had all Winthrop aroused as to his true name and background, but they never learned more than what the slave told them, and of that they could not be sure. Oliver Wendell Holmes visited the island shortly after the fire of 1835, and the burned timbers together with the story, so impressed him that he wrote "An Island Ruin" a few lines of which follow; ^64. This house has been identified as belonging to the Hutchinson family.

They told strange things of that mysterious man; Believe who will, deny them such as can; He came, a silent pilgrim to the West, Some old world mystery throbbing in his breast: Close to the thronging mart he lived alone; He lived; he died. The rest is all unknown. An interesting sequel occurred a few years ago, when a young boy was standing on the Winthrop seashore facing Apple Island. A car from Pennsylvania drove up, and a lady alighted. She asked the youth if he could row her over to Apple Island, but as the tide was dead low, he told her it was impossible. After spending a few minutes looking over at the great elm on Apple Island, she climbed back into the car, and the vehicle moved slowly away. The lady was the great-granddaughter of William Marsh. Nathaniel Parker sold out his entire interest in the salt works to Russell Sturgis, March 15, 1815, for $7,000. Four years later. Reverend Frederick W. A. S. Brown, who was a signal man at Deer Island, composed his unusual rhymes about Point Shirley. They should interest the reader: Point Shirley, to forget, oh muse. Indeed would be a fault Which Sturgis never would forgive Who manufacturers salt. With him how many hours live sat Ah, happy hours they were Engaged in friendly, social, chat. That eased the breast of care. To all her tribute of respect. The muse would offer here; And oft on Shirley will reflect. And drop affection’s tear.

Charles Russell Sturgis, who was born in 1803, moved to Winthrop with his father in 1812 and grew up to love the Point. One day he began sketching the houses on what is now Siren Avenue, showing the salt works at the extreme left of the picture. The sketch is at present in the vault at the Winthrop Public Library, a notable document of over one hundred years ago. Many tons of salt were sold by Sturgis during the early 19th century from his vats at Point Shirley. These large vats were in the shape of circular tanks, with covers resembling four-leaf clovers, which could be slid over the vats at short notice. Salt at this time was selling at about three dollars a barrel, this of course for the coarse variety. There was a large reservoir on the beach, which was filled at every tide. The water from the reservoir was forced a few rods through some logs, by a windmill, finally reaching the vats. It must have been a pretty sight, on a summer »s day, when the pictures-que windmill was spinning slowly around. In 1832, John W. Tewksbury and his father-in-law, Samuel Leeds, purchased the salt works from the widow of Russel Sturgis. Stories have been told by his descendants of the rush to cover over the salt vats at the approach of a sudden shower, as it was as important that the rain water should be kept away from the salt as that the water itself should properly evaporate. Gradually, however, new ideas came into vogue, and the salt works at Winthrop became impractical.

Across the Gut, Captain William Tewksbury was gaining a reputation for his genial hospitality and his ability to save lives. Our rhyming signal man, of Deer Island, Frederick Brown, composed the following about William Tewksbury: Ye sons of festive mirth and dance. To Tewksbury’s hall repair; His kind attentions will enhance. Your pleasures while you’re there. There shaded by some willow trees. The bowling alleys lay. With seats, where you may sit at ease. When not inclined to play. When not inclined to dance or sing. Upon a lofty tree There hangs a strong, well-guarded swing. From every danger free Which, swiftly through the yielding air. In steady, lofty flight. Will gentleman or lady fair, Convey with pure delight. ^65 Tewksbury’s famous rescue of 1817 has been remembered down through the years. On May 26, of that year, a pleasure boat went down, with Tewksbury eventually rescuing seven of the eight on board. For this truly amazing rescue he was praised from Boston to Baltimore. But Tewksbury was getting along in years and desired to retire to the mainland at Point Shirley. He purchased some of the property formerly owned by Russell Sturgis, and when John W. Tewksbury, his cousin, bought property there with Samuel Leeds, the captain believed they should make an agreement. Alexander Wadsworth at that time was considered the best surveyor around the city of Boston, so in the ^65. F. W. A. S. Brown, Valedictory Poem, P. 34.

spring of 1841 the three men asked him to survey Point Shirley. The trouble was in the section known as Short Beach, running from what is now Ridgeway’s Comer to the bend on Shirley Street. The survey was finished in the middle of April and on April 20, 1841, the three men, William Tewksbury, John W. Tewksbury, and Samuel Leeds, entered into an agreement whereby they divided all Point Shirley. The plan of the Point at that time can still be seen, with two houses, William Tewksbury’s and John W. Tewksbury’s indicated. ^66 Four years later Captain William Tewksbury rented part of his land to the Revere Copper Company for $50. a year, with the provision that the treasurer of the Revere Copper Company, James Davis, pay the taxes. The rental was for ten years, starting December 21, 1845. As the Sturgis name fades out of the Point Shirley picture we should remember Captain Josiah Sturgis, son of Samuel Sturgis, whose naval chapeau and sword are under glass in the Pullen Point room of the Winthrop Public Library. Born in 1794, Josiah Sturgis early took to the sea. In 1809, he was on the schooner Mary, which was chased by the British frigate Cleopatra while off the Cape Verde Islands, and eventually sunk by the British frigate. He finally arrived back in Boston. He then shipped to China. Coming back to Boston Harbor in 1832, Josiah Sturgis was commissioned First Lieutenant in the Revenue Service, July 4, 1832, and became captain ^66. Suffolk Deeds, Liber 96, f. 15.

in 1859. Captain Sturgis visited Point Shirley almost every time he was ashore. Sturgis died aboard the Revenue Cutter, Hamilton, June 28, 1850. ^67 When the triple hurricanes of December, 1839, caught the residents of Winthrop unprepared, many sloops were disabled. The first gale began December 15, drowning over fifty persons before it went down, and scattering 22 wrecks about Massachusetts Bay. The Catherine Nichols was wrecked on Nahant, and it is believed that a chest of money floated across the harbor to Grover’s Cliff, Winthrop. December 22 saw another fierce gale, followed five days later by what was claimed by some to be the worst storm of all. In 1830 Chelsea proper had less than 50 residents, with the population of Noddle’s Island about 10 and Breed’s Island 5 or 6. With the coming of the East Boston Land Company, Noddle’s Island grew rapidly, while what is now Chelsea doubled and tripled its population from year to year. A ferry was started between East Boston and the city and it was soon deemed necessary to build a bridge across from Winthrop to Breed’s Island. Joseph Burrill, Joseph Belcher and John W. Tewksbury obtained a charter for the Winthrop bridge in 1835. The first traffic across to Breed’s Island began four years later. It was a free bridge until 1843, but when some of the subscribers ^67. James Lloyd Homer has written a fine sketch of Captain Josiah Sturgis in his Notes on the Seashore.