| Wastewater | Deer Island, Boston Harbor - Page 10 |

| Other than coming up with a solution for disposal of the sludge, the major problem facing the MDC and state officials was the EPA’s requirement that the two treatment plants in the harbor be upgraded to provide secondary treatment of the wastewater. MDC minutes from Sept. 20, 1972 show Metcalf & Eddy being selected for a wastewater nanagement study for Eastern Massachusetts. In November 3, 1972 minutes the M&E contract for the “Master Plan” is upped from $500,000 to $750,000. Not a small amount of money, $4.7 million in 2020 dollars. The Wastewater Engineering and Management Plan for Boston Harbor - Eastern Massachusetts Metropolitan Area (EMMA) Study was born. This the same firm that over 30 years earlier was first to recommend in a report co-authored by company co-founder Harrison Eddy that sewage treatment plants be built on Deer Island and Nut Island. Now a new plan was in the works and the MDC expressed optimism in its 1974 Annual Report, |

| “EMMA's far-reaching scope is considering advanced treatment techniques, land disposal, regional inland satellite plants which would augment low river flow with highly-treated, recovered effluent, re-use and reclamation. Other topics are industrial waste, geographical limits of sewerage systems, "fair share" user charges for communities and industry, administrative structures, population projections, construction priorities and financing.” |

| When the report came out in the late 1975, and then finalized in 1976, it was the comprehensive plan that Governor Sargent had been looking for, unfortunately for him he was no longer governor. He had beaten by Democrat Michael S. Dukakis (b. 1933) in the fall of 1974. It was not a good year to be an incumbent, especially a Republican incumbent. The economy was still reeling from the 1973 oil crisis, Nixon had just resigned, and in Boston Sargent had to call out the National Guard to quell disturbances resulting from school bussing. |

| The overall EMMA study was made up of 16 volumes with 23 individual reports, most of which are available online. All links to Internet Archive: |

| EMMA was a preliminary engineering report with its intention being to guide MDC investments through the next 25 years resulting, by the year, in a modern EPA-compliant metropolitan sewage system. The total cost would be substantial, $855 million, over $4 billion in 2020 dollars. The hope was that 75 percent of that cost would get paid for by the federal government. In its final recommendations, M&E broke down its fifty-two recommended projects into five categories. |

| First offered in the recommendations was a plan for dealing with the over 100 combined sewer overflows in the metropolitan area. Relative to the overall volume of sewage handled by the system, overflow volume was relatively small and intermittent. Unfortunately, when overflow was discharged at the 100 locations during a rainstorm it contained undisinfected fecal waste, debris and solids constituting a health hazard. The option of replacing all the combined sewers in the metropolitan area with separate sanitary and stormwater sewers was far too expensive and disruptive. Remarkably the Deep-Tunnel Plan was still considered an option despite its cost of $430 million (in 1967 dollars) and its inability to receive federal funding. The M&E recommendation was to spend $300 on a decentralized CSO solution featuring new conduits channeling the overflow to existing, expanded, and new detention and regulation facilities. The project could be done in stages starting with the most problematic outfalls first. |

| The next recommendation from M&E was to build new two satellite wastewater treatment plants. One on the upper Neponset River and the other along the middle Charles River. Canton or Norwood were suggested as possible locations for the upper Neponset River treatment. It would be relatively small plant handling an average of 25.2 million gallons of wastewater a day with a peak capacity of 65.7 mgd. This compared to 112 mgd with a 300 mgd peak for NITP, and 343 mgd with a 848 mgd peak for DITP. As planned, it would be a full EPA-approved facility offering secondary treatment. Its operation would help reduce some of the flow to the NITP, and the addition of Its Class B effluent (swimmable and fishable) would increase the flow of the Neponset River. Natick and Medfield were two of towns mentioned for the middle Charles River Treatment Plant. It would be slightly larger than the upper Neponset River Plant with an estimated average flow of 31 mgd with a peak of 75.6 mgd. It too would provide secondary treatment, help reduce the flow of wastewater to NITP, and its swimmable effluent would increase the flow in the Charles River. Projected total cost, $41.1 million for the upper Neponset River plant and $49.6 million for the middle Charles plant. |

| Analysis by M&E of future needs for the overall system showed that many of the interceptor and relief sewer lines needed to be upgraded, in some cases by adding parallel lines. Estimated cost, $95.1 million. In addition, many of the system’s pumping stations were either old or in need of upgrades. Total cost, $19.2 million. |

|

|

| The biggest engineering challenge for M&E was how to upgrade the two existing sewage treatment plants to offer the EPA-required secondary treatment. With the addition of the recommended satellite treatment plant, the Nut Island would not need to have its stated sewage handling capacity increased. There were both mechanical and structural issues that kept the plant ever meeting that capacity level. Repairs and upgrades would fix that problem. The bigger problem was the lack of space available. The existing plant had been built by adding 13 acres of landfill to the island’s original 4 acres. According to M&E, to accommodate secondary treatment an additional 25 acres of landfill would be needed. There were alternatives. Two involved separating the secondary portion of the sewage treatment and placing it on Long Island or on Peddocks Island. Each of these alternatives would significantly increase construction costs for needed pipelines and bridges or causeways. Another option was to build an entire new plant at Broad Meadows in Quincy. Community opposition was likely. Projected total cost for the landfill option, $137.2 million. |

|

|

|

Despite being much newer than the sewage treatment plant on Nut Island, the DITP had similar issues reaching its stated capacity levels, but for a different reason. The maximum peak flow of the plant was limited to the capacity of the three headworks that fed it, the two deep rock relief tunnels from Boston and Chelsea, and the remaining leg of the North Metropolitan System running through Winthrop. The maximum total capacity of the three combined was a 930 mgd. The report noted that while the capacity was 930 mgd that level of treatment of treatment was never reached because of poor reliability of the Nordberg engines. One of the first recommendations was to replace the engines with electric motors. |

| Unlike the extensive use of landfill required to accommodate a treatment plant on Nut Island, Deer Island had a natural size of 210 acres. But the M&E engineers also had to provide space for a County House of Correction, and take into account an inactive military installation, a 100-foot drumlin right in the middle, and a Boston Harbor Island improvement plan that sought to use a portion of the island for recreational purposes. The major design challenge was that the upgrade to secondary treatment involved the engineers finding room for 12 aeration tanks, each 370 feet long, 8 feet wide, and 15 feet deep, and 48 final settling tanks, each 145 feet in diameter and 14 feet deep. In addition, there needed to be room for the sludge incinerators proposed by Havens & Emerson. |

|

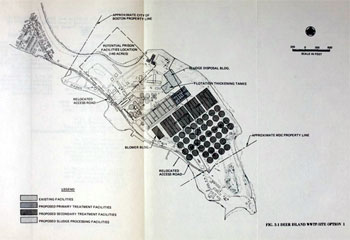

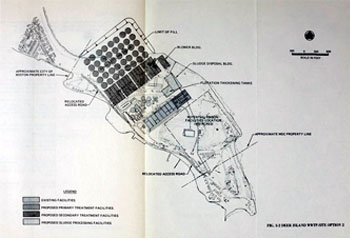

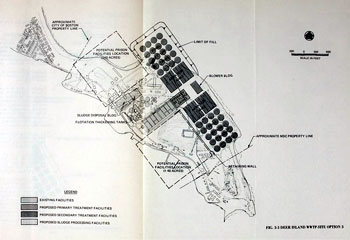

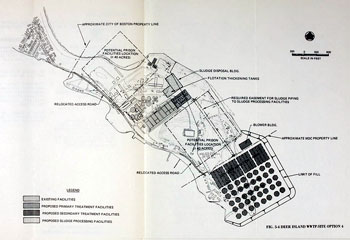

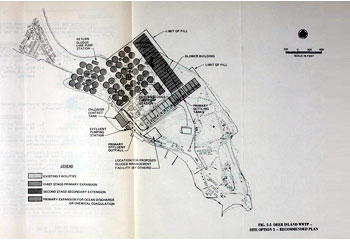

The M&E engineers came up with seven options for what to do on Deer Island. Five were different arrangements of the facilities needed to offer secondary treatment. One of the alternatives was similar to the Deep Tunnel Plan proposed a decade earlier. Primary effluent would flow through a deep underground tunnel dug from Nut Island to Deer Island, then in another to be discharged 11.6 miles out into Massachusetts Bay. It would be expensive and would not be approved by the EPA if it was not secondary treatment effluent. A similar arrangement of tunnels would be incorporated in the final solution, with secondary treatment. The seventh plan proposed to go beyond secondary treatment and provide what was called advanced treatment, likely similar to what today is called tertiary treatment. Its effluent is near drinkable water. It would require an additional 44 acres of landfill. It is clear why this option was ever proposed. Possibly because the zero-discharge wording in the Clean Water Act. |

| The five options proposed by M&E engineers that included secondary treatment differed in their placement of the additional aeration and final settling tanks needed. Two options had the additional tanks placed to the southeast and northeast of the island. Two other options had the tanks on the northwest side of the island. Advantages and disadvantages were detailed for each and nothing was easy with many tradeoffs to consider for each. |

|

|

Level the center drumlin and place the aeration and final tank facilities in its place southeast of the existing treatment plant. Prison facilities get pushed further to the northeast partially on fill. |

|

|

|

|

Placing the aeration and final tank facilities northwest of the existing plant and in a symmetrical arrangement. |

|

|

|

Spilt the aeration and final tank facilities into two groupings on the northside of the island. Use portion of the center drumlin for fill. |

|

|

|

|

Place aeration and final tank facilities on the southern tip of the island with a portion on fill. |

|

|

|

Like option two it called for locating the aeration and final tank facilities northwest of the existing plant but in an asymmetrical arrangement. Prison facilities would be moved to center drumlin. |

|

|

|

| After weighing and the advantages and disadvantages to each, the M&E focused on the two plans both of which had the new secondary treatment tanks to the northwest of the existing plant. For both options, the prison would have to be moved, and in both cases the 60 new aeration and final settling tanks would be directly adjacent to the Point Shirley residential area. Finally, the one that required less fill was selected. Total projected cost, $191.9 million. |

| Much more than a design exercise for infrastructure improvements of the MDC sewage system, the EMMA study took a deeper look at how the Boston metropolitan area was changing and what the wastewater needs of the area would be in the future. While Metcalf & Eddy was responsible for the engineering design volumes there were more contributors. The big accounting firm Peat, Marwick, Mitchell & Co. authored volumes on financial and management aspects of the plan. The Massachusetts Division of Water Pollution Control looked at the probably biological impact of the wastewater alternatives being considered. The MDC authored a volume on the visual and cultural impact. The New England Division of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers on socio-economic and hygienic impact. |

| The New England Division of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers were authors of another volume in the study, Public Involvement. The goal was to offer an open planning process that sought input from the public. The Corps had had managed the process for similar studies earlier primarily by coordinating meetings with technical subcommittees and other agencies. EMMA would be different, it would expand the involvement to include citizens’ committees from academic, commercial, environmental, industrial, and legislative fields. And to further expand public involvement the Corps would hold public meetings, forums, briefings, workshops and would produce informational bulletins, press releases, and engage with the media. The first public meetings started in late 1973 and would continue in 1975 when the EMMA study was published. The volume of the study on Public Involvement does not mention detail the public meetings other than to say there was “virtually universal opposition.” The idea the satellite sewage treatment plants on the Charles and Neponset Rivers garnered significant opposition, but what received the most pushback was an option that the study would reject, the land disposal of sewage. |

|

Since their involvement in the Muskegon, Mich. wastewater land disposal project the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers had been looking for more opportunities. The services were offered, and the Corps began working on a plan for the Boston metropolitan area. When it came out, no one was happy. Proposed were five linked regional secondary sewage treatment plants extending from Woburn to Medford, Watertown, Dedham, and Canton. Effluent and sludge would be pumped in separate lines to Canton where it would be temporarily stored in four lagoons, each 28 acres in size and 25 feet deep. The sludge would be pumped to Dedham to be partially dried and incinerated. From Canton the effluent would be pumped in a deep rock tunnel extending to southeastern Massachusetts and under the Cape Cod Canal to Bourne. More lagoons would store the effluent until it would be used for spray irrigation on crops or to pumped over a specific area for rapid infiltration. Total projected cost, $680 million, or about $3.2 billion in 2020 dollars. Also, it was not a solution for the entire metropolitan area. Because of the harmful effects of salt on crops, no wastewater could be accepted from any area where there was a risk of saltwater infiltration. That excluded Boston and a significant number of other cities and towns that bordered the ocean. Even the authors of the report could not recommend land disposal as a solution. They did recommend a pilot proof of concept project be undertaken. |

|