| Wastewater | Deer Island, Boston Harbor - Page 3 |

| Deer Island Pumping Station |

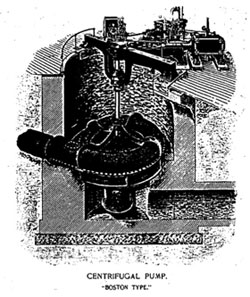

| The final project on Deer Island was building the pumping station. Work began on the foundation in May of 1894 and in less than a year the building completed, pumps installed, and tests begun. By June of 1895 the station was fully functional. In its 1896 report the Metropolitan Sewerage Commissioners could claim that the North Metropolitan system was complete. Sewage from as far away as the system’s most northern point in Stoneham was being discharged at the outlet off Deer Island Beacon, that was now, Deer Island Light. Nearly completed in 1895, Carson left the project to become the Chief Engineer of his next project, building the first-in-the-country subway in Boston. |

Photographs and artwork from the Eighth Annual Report of the Metropolitan Sewerage Commission - 1897 |

|

|

|

|

The sewer system that Carson and his engineers designed in the late 1800s was advanced for its time and even today its framework survives in the current system. Though two features of the design for the Deer Island section did require modification. Costs considerations and limitations of the available technology were likely factors in both cases. As built in 1895 the Deer Island pumping station had two pumps each with a capacity of 45 million gallons per day (mgd). A capability that would allow a single pump to empty the originally planned but never built 20-million-gallon reservoir at Deer Island twice a day. This would allow one pump to be down for maintenance or repair. Over the next three years, as more town were connected to the system, the average daily discharge grew from 31.8 mgd in 1897 to 47.6 mgd in 1899. That meant that a single pump at Deer Island could no longer handle the amount of sewage for a given day. Looking at the projected needs for 1930, the system’s designers should have specified four or even five pumps, not just two. The Board’s Annual Reports contain no discussion about why this wasn’t done. Maybe it was the added cost and having to convince rate payers to buy pumps that would not be used for years to come. Maybe the engineers knew, and as it turned out to be true, that better pumps were soon to be available. In 1901 a third pump with a capacity of 45 mgd was added. By 1907 the 64.3 mgd daily discharge wasn’t the problem, it was the one day maximum of 146.1 mgd that caused concern. By 1910 a fourth pump was added, this one with the increased capacity of 100 mgd. This proved adequate until the next major upgrade for Deer Island. |

| Historic American Engineering Record (HAER) collection for the Deer Island Pumping Station |

|

| Selected photographs of the abandoned Deer Island Pumping Station |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| The other feature of the Deer Island design that needed correction was the location of the outlet. In the initial 1889 report that location is described as “near Deer Island Beacon,” a structure made of rock and stone that had been built in the 1830s as a navigation aid. It doesn’t appear that anyone went to look. What they would have seen was a new manned lighthouse being built on the spot. Its light was first illuminated in January of 1890. In a picture in the 1894 Annual Report the lighthouse can be seen beyond where the cofferdam used in the construction of the outlet ends. Even Carson in his 1893 MIT Technology Quarterly article got it wrong when he said the North Metropolitan system discharges “continuously near the Deer Island Beacon,” not lighthouse. The outlet, completed in 1895, ended 200 feet west of the lighthouse along the western edge of the Deer Island Spit in water that was only 6-inches deep at mean low water (the average of all low water marks), making it almost exposed. |

| In 1913 the problem with a shallow outlet discharging billions of gallons of untreated sewage into the harbor “surfaced.” The board received complaints about the conditions of the water around the outlet from boating interests, the U.S. Government concerned for the nearby proposed military installation, and from the Department of Commerce who ran the lighthouse. They stated that the outlet’s location was “a menace to the health of the keepers and a detriment to the maintenance of the station.” The solution was to extend the discharge pipe further into harbor so the outlet would be in deeper water where stronger currents would dissipate the sewage more rapidly. |

|

| Photographs and artwork from Journal of the Boston Society of Engineers article

|

|

|

|

| After delays getting permits, construction of the new outlet began in 1916. First a temporary outlet was built to divert the flow. A pipe was laid running almost due south to an outlet located on the eastern side of the Deer Island spit. Unlike the earlier masonry-only pipes, the engineers could now use the latest technology of cast-in-place reinforced concrete and cast-iron pipes. The outlet was located at point where the water was 3-feet deep at mean low water with the idea that it would later be extended to deeper water and function as a second outlet. To extend the existing outlet, a 332 feet trench was dug at its deepest 58 feet below low water. Cast iron pipes were used, 9-feet long, 7-feet in diameter, and each weighing 17,000 lbs. Three were connected before being brought out to the site. There were delays as workers faced the same exposed location, swift currents, and storms as did the earlier workers. By the end of the first year only four sections had been laid just beginning down the slope. By the end of the following year, 1917, work was completed, and sewage began flowing out of the pipe’s fourteen discharge outlets, at their deepest, 54 feet below mean low water. |

|

In 1899, shortly after completing the North Metropolitan System, the Metropolitan Sewerage Commissioners were given the task of creating a third sewage system to serve the cities south and west of Boston. The South Metropolitan System, sometimes called the High-Level Sewer, primarily used gravity instead of pumps to transport the sewage to an outfall on Nut Island off Houghs Neck in Quincy. This time a causeway was built connecting the island to the mainland and thanks to recently available large diameter cast iron pipes, the engineers were able to locate two outlets 1,500 feet off the island in water 40 feet below mean low tide. The system was put into use in 1905. With the opening of the South Metropolitan System, and the Deer Island outlet extension, the system for discharging the sewage from the Boston metropolitan area into the ocean was complete. The fact that it was untreated sewage was a not a secret. For cities and towns bordering the ocean simply dumping sewage into the ocean where it would be diluted and dispersed was an accepted and widely practiced solution. |

|